Wall Street industry group SFIG joins the fray in U.S. District Court in Delaware, arguing in an amicus

brief that CFPB has no authority over securitization trusts because they are neither

original creditors nor debt collectors [and should effectively be immune against enforcement action by the Bureau].

On November 21, 2017, STRUCTURED FINANCE INDUSTRY GROUP, INC. (SFIG), an

organization that represents a diverse set of securities market participants joined the pending enforcement action by the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau against all of the National Collegiate Student Loan Trusts as a

proposed amicus curiae, adding its voice to the chorus of intervenors complaining

of the Proposed Consent Judgment (PCJ) between the Trusts' residual owners and the CFPB. See prior blog post on -- > Interventions in CFPB v. National Collegiate Student Loan Trusts.

Like some of the intervenors, SFIG argues that the remedial measures

spelled out in the PCJ are at odds with the Trust-Related Agreements and the

obligations imposed by them on the various parties to the transaction, that the terms of the Proposed Consent Judgment violate the settled expectations of securities market participants,

and that the cash flow from current payments and collections on the student

loans should not be diverted into an escrow account and tapped to pay civil fines

to the government.

"The proposal to use trust assets to pay fines is impermissible. All of that money is pledged. The indentures make clear that trust assets are not available to pay for the sins of servicers."

Among other things, SFIG contends that the Trusts are merely passive investment

vehicles without employees and mere holders of debt, and that they cannot be

held vicariously liable for any misconduct by the servicers because they don’t

control them, as the servicers have the status of independent contractors,

rather than agents.

Specifically, the group argues that the Trusts themselves are not “covered

persons” under the CFPA and that they cannot by held liable vicariously merely

because the servicers that collect on their behalf qualify as “covered persons” under the act that gives the Bureau authority to bring enforcement actions.

"As a matter of law, the Trusts are not “covered persons,” did not take any of the actions challenged by the Bureau, and did not engage in conduct that could be construed to violate a federal consumer protection law."

What the industry group fails to acknowledge, however, is that all of the National

Collegiate Student Loan collection lawsuits are filed with the particular Trust as

the Plaintiff, i.e. in the Trusts' own name, and that neither trustees, nor the administrator,

nor the servicers (PHEAA, TSI) are parties to the collection litigation. When the Trusts' capacity to sue is challenged in Texas courts, their attorneys cite the Delaware Statutory Trust Act to counter such motions.

Under Texas law, "[t]he term `trust' refers not to a separate legal entity but rather to the fiduciary relationship governing the trustee with respect to the trust property." Ray Malooly Tr. v. Juhl, 186 S.W.3d 568, 570 (Tex. 2006). Indeed, the "Texas Trust Code[] explicitly defines a trust as a relationship rather than a legal entity." Id. In Texas, a "trustee is vested with legal title and right of possession of the trust property but holds it for the benefit of the beneficiaries, who are vested with equitable title to the trust property." Faulkner v. Bost, 137 S.W.3d 254, 258-59 (Tex. App.—Tyler 2004, no pet.)

THE TRUSTS ARE THE PARTIES IN LITIGATION, NOT THE SERVICERS

While the Student Loan Trusts' attorneys may incur liability under the FDCPA because

they too fall under the definition of debt collectors, the attorneys are agents

of the Delaware statutory Trusts and the Trust (not the servicer) is the principal. Because the

Trusts appear as plaintiff, they are not merely passive legal entities, the Trusts’

attorneys’ actions are – by virtue of agency – actions of the Trusts as

Plaintiffs. It is the Trusts that obtain default judgments and file for garnishments and other enforcement actions.Since the trusts are not natural persons, of course, they can only litigate by and through attorneys.

|

| Example of Judgment in Garnishment rendered for one of the Trusts |

|

| Example of Default Judgment for Trust 2005-3 |

When the Trusts apply for a writ of garnishment against a debtor, they affirmatively assert that they own the judgment.

The Trusts, not the servicers, are also subject to legal defenses to debt

claims and counterclaims. Judgments are entered in favor or against the Trusts,

and not in favor or against any other transaction party or servicer. The Trust's attorneys sign agreed dismissals and settlements.

|

| Example of Joint Motion to Dismiss in contested case |

The

servicers (PHEAA/AES and TSI, previously NCO) merely furnish documentation and affidavits as evidence

to support the Trusts' claims in court. These documents are filed by the

attorneys as agents of the Trusts. To the extent that the affidavits produced

by NCO and TSI were false or fraudulent, it is the Trust that filed and relied on them to support their claims, procured a favorable judicial resolution, and reaped the benefits as the judgment creditors on ill-gotten

judgments irrespective of how the collected funds were

later channeled and distributed.

|

| TRUSTS AS PARTIES: RARE EXAMPLE OF A MONEY JUDGMENT AGAINST NATIONAL COLLEGIATE STUDENT LOAN TRUSTS |

And unlike other securitization trusts, the National Collegiate Student

Loan Trusts do not sue through a trustee, at least not in Texas. In light of

that, SFIG’s argument that the Trusts are merely passive legal entities that cannot be blamed for any wrongdoing sounds

even more hollow.

SFIG submits that the Bureau lacks the statutory authority to file a complaint against or enter into a civil order with the Trusts. The Bureau has adequate remedies in bringing claims against the parties who allegedly actually conducted activities which violated the FDCPA and the Act. There is no justification for expanding its authority to include passive entities that did not themselves engage in any such activities.

THE MARKET PARTICIPANTS WERE ON NOTICE OF THE RISKS OF NON-COMPLIANCE WITH FEDERAL AND STATE CONSUMER PROTECTION LAWS PRIOR TO SECURITIZATION

SFIG also complains that market participants' expectations are being

up-ended by the CFPB's regulatory action against the Trusts and the remedies encompassed by the proposed settlement.

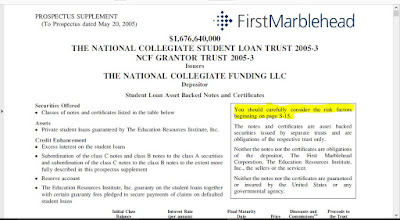

Contrary to the industry group’s claim, the investors in the bonds

issued by Trusts were on notice of the risks of investing – along with other

market participants, such as note insurer Ambac -- because those risks were

disclosed to them in the prospectuses prior to the issuance of the bonds.

The disclosed risks included risks associated with faulty origination that might result in counterclaims

or offset claims in litigation, including violations of the Truth-in-Lending

Act and other defects that may affect enforceability of the notes. All potential investors and interested market participants were on notice that debt-holders – i.e. the Trusts -- may be subject to liability arising

from unfair and deceptive practices, and that cash flows into the collection account could be adversely affected as a result.

See sample regulatory risk disclosure below (for 2007-4 securitization):

Consumer Protection Laws

Numerous federal and state consumer protection laws and related regulations impose substantial requirements upon lenders and servicers involved in consumer finance. These requirements may apply to assignees such as the trusts and may result in both liability for penalties for violations and a material adverse effect upon the enforceability of the trust student loans. For example, federal law such as the Truth-in-Lending Act can create punitive damage liability for assignees and defenses to enforcement of the trust student loans, if errors were made in disclosures that must accompany all of these loans. Certain state disclosure laws, such as those protecting cosigners, may also affect the enforceability of the trust student loans if appropriate disclosures were not given or records of those disclosures were not retained. If the interest rate on the loans in question exceeds applicable usury laws, that violation can materially adversely affect the enforceability of the loans. If the loans were marketed or serviced in a manner that is unfair or deceptive, or if marketing, origination or servicing violated any applicable law, then state unfair and deceptive practices acts may impose liability on the loan holder, as well as creating defenses to enforcement. Under certain circumstances, the holder of a trust student loan is subject to all claims and defenses that the borrower on that loan could have asserted against the educational institution that received the proceeds of the loan. Many of the trust student loans in question include so-called “risk based pricing,” in which borrowers with impaired creditworthiness are charged higher prices. If pricing has an adverse impact on classes protected under the federal Equal Credit Opportunity Act and other similar laws, claims under those acts may be asserted against the originator and, possibly, the loan holder. For a discussion of the trust’s rights if the trust student loans were not originated or serviced in all material respects in compliance with applicable laws, see “Transfer and Administration Agreements” in this prospectus.

***

Consumer protection laws

may affect enforceability of the trust student loans

S-21

Additionally, the relevant contracts provide for the net proceeds from collection and

litigation on liquidated student loans to be deposited into the Trusts’

collection account, meaning that the costs of litigation are first deducted

before the cash stream is funneled to the investors. See GLOSSARY

FOR PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT, Page G-2

“Recoveries” means, with respect to any liquidated student loan, moneys collected in respect thereof, from whatever source, during any Collection Period following the Collection Period in which the trust student loan became a liquidated student loan, net of the sum of any amounts expended by the servicers (or any sub-servicer acting on its behalf) for the account of any obligor and any amounts required by law to be remitted to the obligor.

In that regard, then, the argument that the settled expectations of

the market participants are being disturbed by required refunds to borrowers

and penalty payments resulting from misconduct in collection/litigation is

highly questionable.

Nor does SFIG ever explain why notions of amorphous settled expectations of market participants should guide the Court in the presence of express contracts

to which certain market participants are parties while others are not. Expectations, and risk assessments, should be based on the securitization-related contracts, and on due diligence, including review of the information about the pool of loans disclosed in the prospectuses, rather than on unrealistic expectations of high yields based on rosy assumptions and disregard of adequately disclosed risks, including compliance and regulatory risks.

Additionally, to the extent the misconduct and associated financial

consequences are attributable to acts and/or omissions of involved parties

other than the Trusts, the relevant agreements also provide for the repurchase of loans

(by the program lender or by the services) and for indemnity obligations. See page

S-5.

A final Consent Judgment between the CFPB and the Trusts could take such indemnification obligations into account and thereby accommodate the criticism that the remedial measures are at odds with the various transaction and trust-related contracts.

REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES OF THE DEPOSITOR Under the deposit and sale agreement for each trust, we, as the seller of the loans to the trust, will make specific representations and warranties to the trust concerning the student loans. We will have an obligation to repurchase any trust student loan if the trust is materially and adversely affected by a breach of our representations or warranties, unless we can cure the breach within the period specified in the applicable prospectus supplement.

REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES OF THE SELLERS UNDER THE STUDENT LOAN PURCHASE AGREEMENTS In each student loan purchase agreement, each seller of the student loans will make representations and warranties to us concerning the student loans covered by that student loan purchase agreement. These representations and warranties will be similar to the representations and warranties made by us under the related deposit and sale agreement. The sellers will have repurchase and reimbursement obligations under the student loan purchase agreement that will be similar to ours under the deposit and sale agreement. We will assign our rights under the student loan purchase agreement to each related trust.

COVENANTS OF THE SERVICERS Each servicer will service the student loans acquired by us pursuant to a servicing agreement. Each servicer will pay for any claim, loss, liability or expense, including reasonable attorneys’ fees, which arises out of or relates to the servicer’s acts or omissions with respect to the services provided under the

Also see Page S-24

Repurchase of trust student loans by

the sellers

Upon the occurrence of a breach of representations and warranties with respect to a trust student loan, the depositor may have the option to repurchase the related trust student loan from the trust and, regardless of the repurchase, must indemnify the trust with respect to losses caused by the breach. Similarly, the seller of the loan to the depositor may then have the option to repurchase the related trust student loan from the depositor and, regardless of the repurchase, must indemnify the depositor with respect to losses caused by the breach. If the respective seller were to become insolvent or otherwise be unable to repurchase the trust student loan or to make required indemnity payments, it is unlikely that a repurchase of the trust student loan from the trust or payments to the trust would occur.

Indeed, repurchase obligations are included

among the list of credit or cash flow enhancement for the trust. See S-4.

SUMMARY OF SFIG'S ARGUMENTS IN ITS PROPOSED AMICUS BRIEF

[conversion from pdf]

Before the

Court are a Complaint and a Proposed Consent Judgment in which the Bureau

asserts that the conduct of the Trusts’ servicers constituted unfair, deceptive

or abusive acts or practices that violated the Consumer Financial Protection

Act (the “CFPA” or the “Act”) in connection with activities related to the

collection of debt. The Proposed Judgment would hold the Trusts responsible for

its servicers’ debt collection activities. SFIG, as a proposed amicus curiae,

takes no position on the conduct of the servicers. Rather, SFIG, its members

and constituents are concerned that the underlying arguments fail to account

for whether the Bureau is empowered in the first place to exercise its

authority against the Trusts with respect to the activities at issue, and what

impact such a finding would have on the reasonable expectations of the market

participants involved in securitizations.

First,

under the Act, the statute that defines the Bureau’s authority, the Bureau’s

authority extends to conduct engaged in by a “covered person,” or a covered

person’s “service provider.”2

2 12 U.S.C. § 5531(a). A “service

provider” is defined as: “any person that provides a material service to a

covered person in connection with the offering or provision by such covered

person of a consumer financial product or service, including a person that

(i) participates in designing, operating, or maintaining the consumer financial

product or service; or (ii) processes transactions relating to the consumer

financial product or service.” 12 U.S.C. § 5481(26) (emphasis added).

The Trusts

are not “covered persons” within the meaning of the CFPA because the

Trusts—which the Bureau concedes are passive entities with no employees—are not

engaged in the core conduct attributable to “covered persons,” namely offering

or providing a consumer financial product or service.

Second,

even if the Trusts were “covered persons” within the meaning of the Act, the

Bureau’s enforcement authority extends only to “covered persons” that have

violated a federal consumer protection law.3

3 12 U.S.C. § 5564(a).

Here, the

Bureau implies that the Trusts vicariously violated the Fair Debt Collection

Practices Act (the “FDCPA”),4

4 Congress enacted the FDCPA in order

“to eliminate abusive debt collection practices by debt collectors, to

insure that those debt collectors who refrain from using abusive debt

collection practices are not competitively disadvantaged, and to promote

consistent State action to protect consumers against debt collection abuses.”

15 U.S.C. § 1692(e)(emphasis added); see generally 15 U.S.C. §§ 1601, et

seq.

and

therefore the Act itself, but provides no evidence of any actual violation by

the Trusts. Accordingly, SFIG submits that the Bureau lacks the statutory

authority to file a complaint against or enter into a civil order with the

Trusts. The Bureau has adequate remedies in bringing claims against the parties

who allegedly actually conducted activities which violated the FDCPA and the

Act. There is no justification for expanding its authority to include passive

entities that did not themselves engage in any such activities.

Third,

SFIG’s members, and all market participants, rely on the stability of law to

anticipate their liabilities and risk, and enter into agreements that provide

the building blocks for the economy. The interests of SFIG’s members, as well

as the interests of other similarly situated market participants and,

ultimately, the investors and borrowers themselves, will be harmed if the

Bureau is permitted to extend its litigation and enforcement powers beyond its

legislative grant, thereby undermining this stability. This extra-statutory

enlargement will disrupt the secondary loan market for many types of consumer

and business loans, including student loans, and also will create uncertainty

and unwarranted potential liability for market participants that justifiably

relied on previously well-established regulation by known regulators.

The impact

on the securitization market could result in increased interest rates and

reduced availability of credit, all to the detriment of borrowers and the overall

economy.

The Bureau

has asserted that it “was designed to be agile and adjust its approach to

supervising the financial industry in order to respond rapidly to changing

consumer needs.”5

5 CONSUMER FIN. PROT. BUREAU, CONSUMER

FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU STRATEGIC PLAN (2013) at 9.

This is an

overstatement of the Bureau’s actual authority in light of its stated purpose

and objectives set forth by Congress in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and

Consumer Protection Act (the “Dodd-Frank Act”). Congress intentionally placed

clear limits on which entities were subject to the Bureau’s jurisdiction. In

this action, the Bureau is not “adjusting its approach.” It is improperly

attempting to expand its jurisdiction through use of the courts. The statutes that

grant enforcement power to the Bureau give it neither enforcement nor

litigation authority over the Trusts.

No comments:

Post a Comment