In Houle v. Capital One the Court issued a summary denial of the defendant's petition for review, letting

stand the judgment and opinion of the intermediate court of appeals in El Paso. This was

expected, given the Texas Supreme Court’s highly selective use of discretionary

review and lack of interest in run-of-the-mill collection cases involving small

amounts (here, about $4,000). See Robert B. Houle v. Capital One Bank (USA), N.A. , No. 08-17-00189-CV (Tex.App.- El Paso, Dec. 19, 2018, pet. denied under No. 19-0224).

Houle provides an example of a credit card collection case in which

the defendant had countered the bank’s motion for summary judgment with an

affidavit of his own, but it did him no good because both the trial court and

the court of appeals denied the counter-affidavit the effect of creating a fact

issue precluding summary judgment.

|

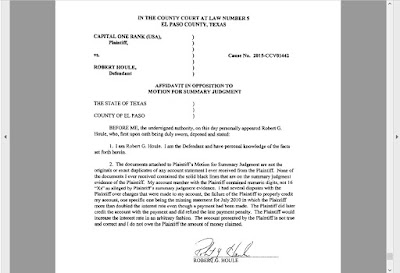

| Controverting Summary Judgment Affidavit of Defendant Robert Houle disputing authenticity of records, legitimacy of interest rate, and correctness of amount |

Although the El Paso Court of Appeals withdrew

its original opinion (still available on Google Scholar here), and substituted a new one in response to the appellant’s

motion for rehearing, it did not change its mind on the disposition. In his

affidavit, Houle had complained--inter alia-- that the bank had arbitrarily raised the interest

rate, that there had been billing disputes on the account, and that pages were

missing from the series of statements proffered as summary judgment proof. All

to no avail.

Genuine Issue of Material Fact

The four elements of a breach of contract claim are: (1) the existence of a valid contract; (2) performance, or tendered performance, by the plaintiff; (3) breach of the contract by the defendant; and (4) damages to the plaintiff resulting from that breach. Restrepo v. All. Riggers & Constructors, Ltd., 538 S.W.3d 724, 740 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2017, no pet.), citing Velvet Snout, LLC v. Sharp, 441 S.W.3d 448, 451 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2014, no pet.). A party is entitled to relief for a stated account where: (1) transactions between the parties give rise to indebtedness of one to the other; (2) an agreement, express or implied, between the parties fixes an amount due, and (3) the one to be charged makes a promise, express or implied, to pay the indebtedness. Eaves v. Unifund CCR Partners, 301 S.W.3d 402, 407-08 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2009, no pet.); McFarland v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., 293 S.W.3d 759, 763 (Tex.App.-Waco 2009, no pet.); Dulong v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., 261 S.W.3d 890, 893 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2008, no pet.).

Because an agreement on which an account stated claim is based can be express or implied, a creditor need not produce a written contract to establish the agreement between the parties; an implied agreement can arise from the acts and conduct of the parties. See Walker v. Citibank, N.A., 458 S.W.3d 689, 692-93 (Tex.App.-Eastland 2015, no pet.).

In response to Capital One's motion for summary judgment, Houle filed an affidavit in which he complained that Capital One's documents were not original or exact duplicates of account statements he had received, and noted both that his statements did not contain solid black lines and his account number had numeric digits rather than the "Xs" contained in Capital One's summary judgment evidence. Houle acknowledged that although he had disputes with Capital One regarding charges and credits to his account, Capital One later credited payment and refunded a late penalty. Houle also complained that Capital One had increased its interest rate in an arbitrary manner, specifically in July 2010 when he made a payment and Capital One purportedly doubled the "interest rate," and without specifying, he asserted in a conclusory manner that the account is not true and correct and that he does not owe the amount Capital One claims is due. There is no evidence in the record from Houle or Capital One regarding payments made in July 2010.

The evidence showed that Capital One and Houle entered into a credit card agreement, that Capital One issued a credit card to Houle, that Houle used the credit card to make purchases, and that Houle made payments on the account. Evidence of the card-member agreement was presented to the trial court through Trittipoe's affidavit. The agreement provides that Capital One would allow Houle to purchase goods and services with credit in exchange for payment. According to the terms of the agreement, Capital One would assess interest charges based on the application of the annual percentage rate, which varies as the index for the rate increases or decreases, and in the event of two late payments, the variable annual percentage rate would increase to an unspecified "penalty annual percentage rate." The June 2010 statement having a July 2010 due date shows an annual percentage rate of 13.52%. Further, the record showed that Houle's account was past due for six consecutive months, from January 2013-June 2013, with an annual percentage rate of 29.40%, incurred past due and over limit fees, and was thereafter "charged off," with a final balance of $4007.72.

Based on the card-member agreement, Capital One's extension of credit on Houle's account, Houle's usage of the credit card and failure to pay on the account in accordance with the terms of the agreement, and Capital One's resulting damages, we conclude that Capital One satisfied each element of its breach of contract cause of action and, if necessary for the account-stated cause of action, conclude or reasonably infer that Houle agreed to pay a fixed amount equal to the purchases and cash advances he made, plus interest. See Dulong, 261 S.W.3d at 894; McFarland, 293 S.W.3d at 763-64 (cases holding creditor could collect debt on account stated where, based on series of transactions reflected on account statements, creditor established that card holder agreed to full amount shown on statements and impliedly promised to pay indebtedness). We conclude that no genuine issue of material fact exists as a matter of law as to any element of Capital One's causes of action against Houle. Taking Houle's affidavit as true, and indulging every reasonable inference and resolving any doubts in his favor, we conclude that Houle failed to satisfy his burden of presenting evidence that raises a genuine issue of material fact. See Nixon, 690 S.W.2d at 548-49.

The disposition of the affidavit issue mirrors an earlier

case involving American Express, in which the defendant, a former Harris County district court judge, had also filed a controverting affidavit, in which he

denied having received the cardmember agreement on which the bank moved for

summary judgment, and had specially denied that he had consented to the interest

rates charged by American Express. In that case, the Ninth Court of Appeals in

Beaumont likewise affirmed the summary judgment for the bank notwithstanding

the presence of a controverting affidavit, but it reversed the award of

attorney’s fees and remanded that portion of the case back to the trial court.

On the matter of fees, the appellate court concluded that

the fee affidavit executed by the bank’s attorney was conclusory, and noted

that the defendant had filed a counter-affidavit disputing the reasonableness

of the amount. Because the defendant was himself an attorney, he was qualified

to offer an expert opinion on the matter. See Devine v. Am. Express CenturionBank, No. 09-10-00166-CV, 2011 WL 2732583 (Tex. App.-Beaumont July 14, 2011, no

pet.) (mem. op.). (“the evidence presented by Amex is not conclusive evidence

of reasonable fees. Additionally, while Devine's affidavit appears conclusory,

it controverts the evidence presented by Amex on attorney's fees. Under these

circumstances, we find the trial court erred in granting summary judgment on

attorney's fees.”).

But even on the matter of fee proof, appellate dispositions

are inconsistent in credit card cases. In Duran v. Citibank, the attorney for the

defendant had submitted a controverting fee affidavit in opposition to the creditor’s

motion for summary judgment, but the appellate court ultimately found it deficient

because it did not specifically attest to what alternative hourly rate would have

been reasonable.

Duran's attorney, John Mastriani,

filed an affidavit in which he stated that he is "familiar with the normal

and customary attorney fees for an action such as this" and opined that

the fees charged ($150.00 per hour for attorneys and $95.00 per hour for paralegals)

were "outrageous and excessive." However, Mastriani failed to provide

evidence of an alternative rate that he would deem reasonable and necessary or

otherwise to controvert Spencer's affidavit with controverting evidence. We

hold that Citibank conclusively established that it was entitled to recover its

attorney's fees as awarded by the trial court. See Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem.

Code Ann. § 38.001 (Vernon Supp. 2007); see also Hackberry Creek Country Club,

Inc. v. Hackberry Creek Home Owners Ass'n, 205 S.W.3d 46, 56 (Tex. App.-Dallas

2006, pet. denied).

Duran v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., No. 01-06-00636-CV,

2008 WL 746532 (Tex.App. - Houston [1st Dist.], March 20, 2008, no pet.) (mem.

op.).

What’s to learn from this?

The lesson to learn is that the counter-affidavit disputing the creditor's claim for attorney's fees should be as detailed as possible.

That lesson is of little use to most pro se

defendants, however, because nonlawyers are deemed incompetent to opine on the

reasonableness of an attorney’s fee. While attorneys get sued on defaulted credit

cards and loans, too, and while they often chose to represent themselves when so sued, statistically that is rare within the universe of collection cases.

As for controverting evidence on the merits of the breach-of-contract

claim, the Houston Court of Appeals noted in Duran that “[i]n response to the motion for

summary judgment, Duran did not present any competent evidence that he did not

receive the agreement or notices of changes in the agreement.” Devine did just

that in this counter-affidavit, but it still did not make any difference in the

resolution of the case.

Devine executed an affidavit that was submitted in support of his

response to Amex's motion for summary judgment. Devine argues that his

affidavit contradicts Amex's summary judgment evidence, precluding summary

judgment.

In support of its motion for summary judgment, and along with a

copy of the purported agreement and a series of monthly statements from Amex to

Devine, Amex submitted the affidavit of an attorney employed by Amex. The

affidavit stated that the attorney was employed by Amex, he was competent to

make the affidavit, was authorized to execute the affidavit on behalf of Amex,

and the statements made therein were within his personal knowledge. The

attorney's affidavit laid the foundation for the business records exception to

the hearsay rule for the records submitted in support of the motion for summary

judgment. The affiant further stated as follows:

A true and correct copy of the applicable

Agreement between AMEX and [Devine] is attached hereto as Exhibit "A"

and incorporated herein. Under the Agreement, AMEX made cash advances to

[Devine], either as actual cash or in payment for purchases made by [Devine]

from third parties. [Devine] accepted each advance and under the Agreement

became bound to pay AMEX the amounts of such advances, plus additional charges.

The Agreement provides that [Devine] may object to any disputed charges, in

writing and within sixty (60) days of notice of the charge. [Devine] made no

objections to any of the charges included in the balance within that time

period.

[Devine] has failed to repay all the advances

made under the Agreement. There is a balance of $21,763.75 owing on [Devine's]

account[.]

In the affidavit submitted in support of his response, Devine

stated in part:

. . . I did not receive the agreement attached

to Plaintiff's summary judgment. I specifically dispute the attached agreement

as it was not the terms and conditions represented to me as the operative terms

and conditions. Plaintiff fraudulently charged [an] additional interest rate

never agreed upon. Further, my agreement with Plaintiff was for a different

interest rate than Plaintiff is now attempting to charge. I have requested an

accounting from Plaintiff but Plaintiff has refused to provide said accounting

of the charges they now seek to bill me. I never agreed to waive all my rights

simply by not putting in writing within 60 days a specific challenge to

Plaintiff's bill when Plaintiff refuses to provide a detailed accounting of the

charges and to properly account for the interest.

The agreement attached as "Exhibit A" to Amex's motion

for summary judgment is entitled "Agreement Between Cash Rebate Cardmember

and American Express Centurion Bank, FSB." The agreement states,

"[w]hen you keep, sign or use the Card issued to you (including any

renewal or replacement Cards), or you use the account associated with this Agreement

(your "Account"), you agree to the terms of this Agreement." The

evidence establishes that Devine is an "American Express Cash Rebate

Credit Card" holder. Though Devine argues that he never received the

agreement, courts have held that delivery of an agreement is shown when the

parties manifest an intent through their actions and words that the contract

become effective. Winchek v. Am. Express Travel Related Servs. Co., 232 S.W.3d 197, 204 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.]

2007, no pet.).

In Winchek, the defendant, Winchek, argued that

the trial court's grant of summary judgment in favor of Amex was improper

because Amex failed to prove it ever delivered the agreement to her. Id. The

court concluded that Winchek's "conduct in using the card and making

payments on the account for the purchases and charges reflected on her monthly

billing statements manifested her intent that the contract become

effective." Id. Winchek further argued that Amex failed

to show proof of her acceptance of the terms of the agreement. Id. In

holding that Amex met its burden to conclusively establish an agreement between

Amex and Winchek, the Court found significant that the agreement expressly

stated that use of the card constituted acceptance of the terms set forth in

the agreement, and that Winchek did not dispute that she had used the

card. Id. In addition, the court noted that Winchek made

payments each month without ever disputing the accuracy of the statements or

the stated terms. Id.

Amex provided evidence by affidavit that the agreement attached

as "Exhibit A" was the operative agreement between Amex and Devine.

Amex also provided balance statements from December 2007 through August 2008

showing that Devine used the "American Express Cash Rebate Card"

issued by Amex and made payments on the account. On this record, Devine's

statement that he did not receive the agreement is insufficient to raise a fact

issue regarding the existence of an agreement between the parties. See

id.; see also Ghia v. Am. Express Travel Related Servs., No. 14-06-00653-CV, 2007 WL 2990295, at *3 (Tex.

App.-Houston [14th Dist.] Oct. 11, 2007, no pet.) (mem. op.)

("Because appellant used her card and made some payments due, she

manifested intent that the agreement become effective, irrespective of whether

she received manual delivery.").

ROBERT G. HOULE, Appellant,

v.

CAPITAL ONE BANK (USA), N.A., Appellee.

Court of Appeals of Texas, Eighth District, El Paso.

Appeal from County Court at Law No. 5, of El Paso County, Texas, (TC No. 2015-CCV01442).

Before McClure, C.J., Rodriguez, and Palafox, JJ.

OPINION

ANN CRAWFORD McCLURE, Chief Justice.

We withdraw our Opinion of September 28, 2018, and substitute this opinion in its place. We deny Appellant's motion for rehearing.

This is a traditional summary judgment case arising from alleged non-payment of a credit card account. Appellant Robert G. Houle appeals the trial court's grant of summary judgment in favor of Appellee, Capital One Bank (USA), N.A. ("Capital One"). We affirm the trial court's judgment.

PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

Houle entered into a credit card account agreement with Capital One in 1998. In 2014, Capital One filed its original petition in Justice Court, Precinct 3, Place 1 of El Paso County, and therein asserted causes of action against Houle for breach of contract and account stated. Capital One sought to recover $4007.72 from Houle on his account, which Capital One identified in its petition as "XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX." Capital One also noted in its petition that Houle's account number had been redacted pursuant to Rule 21c(a)(2) and 508.2(a)(1)(B) of the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure. TEX.R.CIV.P. 21c(a)(2)(Privacy Protection for Filed Documents), 508.2(a)(1)(B)(Debt Claim Cases, Petition, Contents, Credit Accounts). On July 31, 2015, the Justice Court entered final judgment in favor of Capital One and awarded it the principal sum of $4,007.72, without interest, and costs of court.

Houle appealed the Justice Court's judgment to County Court at Law Number 5 (the trial court), and Capital One filed a motion for summary judgment accompanied by a supporting brief. In support of its motion for summary judgment, Capital One presented evidence in the form of an affidavit executed by Diane Trittipoe, who averred that she is an employee of Capital One Services, LLC, an agent and affiliate of Plaintiff Capital One Bank that provides services to Capital One in relation to its credit card and banking practices. Trittipoe's responsibilities as a Litigation Support Representative provide her access to relevant Capital One systems and documents necessary for validation of the information and statements made in her affidavit. In her affidavit, Trittipoe states she has personal knowledge of the manner and method by which Capital One creates and maintains certain business books and records, including computer records of customer accounts.

Trittipoe attached 183 pages of records to her affidavit as evidence of the applicable terms, conditions, and activity related to the credit card account "ending in XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX issued to [Robert G. Houle] by [Capital One.]" Trittipoe does not represent that all records on the account are attached to her affidavit nor represents that the records she has produced include all records for a particular period of time. Although the account number on the statements has been redacted, Trittipoe states that the records are originals or are exact duplicates of the originals.

The records include some, but not all, credit card account statements due in and between the months of February 2008 and June 2013. The records show that the annual percentage rate assessed on the account balance varied each month from a low of 13.43% to a high of 25.15%. The rate often changed from month to month, and rarely remained constant for more than two or more consecutive months. After Houle's account became delinquent, the annual percentage rate of 29.40% was applied to the account balance. The last account statement for the period of May 11, 2013 to June 10, 2013, shows a previous balance of $3,832.72, payment and credits of $0.00, fees and interest charged in the sum of $175.00, and a new balance of $4,007.72, the sum which Capital One sought to recover in its suit. That statement also includes contact information for Capital One, a statement that Houle's account has been "charged off," which is described as a status change from "past due," as well as a notification that although Houle would remain responsible for paying the balance on the account, Capital One would no longer charge Houle past due, over limit, or membership fees.

In response, Houle asserted that Capital One's motion for summary judgment should be denied because a genuine issue of material fact exists regarding "the amount claimed by [Capital One]," in part because the records attached to Trittipoe's affidavit did not contain a statement for the month of July 2010, and the interest rate on the account in June 2010 was shown to be 13.47% but had increased to 29.40% in August 2010. Houle also complained of Trittipoe's alleged lack of personal knowledge to support the affidavit as well as the state of the records attached to the affidavit.

The trial court granted final summary judgment in favor of Capital One. Houle appeals the trial court's judgment.

DISCUSSION

In his sole issue on appeal, Houle contends the trial court erred in granting Appellee's motion for summary judgment. This contention is based on Houle's assertions that Capital One failed to properly authenticate its business records through Trittipoe, that the records were incomplete and contained conflicting inconsistencies, and that genuine issues of material fact exist in relation to the interest rate assessed and changes thereto as well as the amount owed on his Capital One account.

Standard of Review

We review a summary judgment de novo. Valence Operating Company v. Dorsett,164 S.W.3d 656, 661 (Tex. 2005); Roth v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., 439 S.W.3d 508, 511-12 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2014, no pet.). To prevail on a summary judgment motion, the movant must demonstrate that no genuine issues of material fact exist and that it is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(c); Provident Life and Acc. Ins. Co. v. Knott, 128 S.W.3d 211, 215-16 (Tex. 2003); Nixon v. Mr. Property Management Company, Inc., 690 S.W.2d 546, 548 (Tex. 1985).

A movant for summary judgment must conclusively prove all elements of its cause of action as a matter of law. TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(c); see Rockwall Commons Associates, Ltd. v. MRC Mortg. Grantor Trust I, 331 S.W.3d 500, 505-06 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2010, no pet.). If ordinary minds could not differ as to the conclusion to be drawn from the evidence, a matter is conclusively proven. Id. at 505. If the movant conclusively proves its right to summary judgment as a matter of law, the burden then shifts to the non-movant to present evidence that raises a genuine issue of material fact, precluding the summary judgment. Id.

When determining whether a disputed issue of material fact exists that would preclude summary judgment, we regard all evidence in the summary judgment record in the light most favorable to the non-movant, and indulge every reasonable inference and resolve any doubts in favor of the non-movant. Walters v. Cleveland Regional Medical Center, 307 S.W.3d 292, 296 (Tex. 2010); Provident, 128 S.W.3d at 215-16. When a trial court's summary judgment order does not state the specific grounds for its ruling, we must affirm the judgment if any of the theories advanced by Appellee's motion are meritorious. Western Investments, Inc. v. Urena, 162 S.W.3d 547, 550 (Tex. 2005).

The standards for determining the admissibility of evidence is the same in a summary judgment proceeding as at trial. See Seim v. Allstate Texas Lloyds, 551 S.W.3d 161, 163-64 (Tex. 2018)(per curiam), citing United Blood Servs. v. Longoria, 938 S.W.2d 29, 30 (Tex. 1997)(per curiam); Rockwall Commons Associates, Ltd., 331 S.W.3d at 505-06. The admission or exclusion of evidence rests in the sound discretion of the trial court. See Interstate Northborough Partnership v. State, 66 S.W.3d 213, 220 (Tex. 2001), citing City of Brownsville v. Alvarado, 897 S.W.2d 750, 753 (Tex. 1995). Evidence presented in support of a summary judgment must be in a form that would render the evidence admissible in a conventional trial. TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(f); see United Blood Services v. Longoria,938 S.W.2d 29, 30 (Tex. 1997).

We apply an abuse of discretion standard when reviewing a trial court's decision to admit or exclude summary judgment evidence. Harris v. Showcase Chevrolet, 231 S.W.3d 559, 561 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2007, no pet.). The test for abuse of discretion is not whether, in our opinion, the facts present an appropriate case for the trial court's actions. Downer v. Aquamarine Operators, Inc., 701 S.W.2d 238, 241-42 (Tex. 1985). Rather, it is a question of whether the trial court acted without reference to any guiding rules and principles. Id. In other words, we must determine whether the court's rulings were arbitrary or unreasonable. Id. at 242. The mere fact that a trial court may decide a matter within its discretionary authority in a different manner than an appellate judge in a similar circumstance does not demonstrate that an abuse of discretion has occurred. Id.

Preservation of Error

We first address Capital One's assertion that Houle has failed to preserve this issue for our review. The rules of error preservation applicable during trial also apply in summary-judgment proceedings. TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1(a); see Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 164, citing Mansions in the Forest, L.P. v. Montgomery Cty., 365 S.W.3d 314, 317-18 (Tex. 2012)(per curiam). Consequently, to preserve a complaint for appellate review: (1) a party must complain to the trial court by way of a timely request, objection, or motion; and (2) the trial court must rule or refuse to rule on the request, objection, or motion. TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1(a); Mansions in the Forest, L.P., 365 S.W.3d at 317. The party asserting objections should obtain a written ruling at, before, or very near the time the trial court rules on the motion for summary judgment or risk waiver. See TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1(a); Dolcefino v. Randolph, 19 S.W.3d 906, 926 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2000, pet. denied).

If the factual statements in an affidavit are "not obviously based on hearsay[,]" a defect is purely formal. See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Penn, 363 S.W.2d 230, 234 (Tex. 1962); see also Ford Motor Co. v. Leggat, 904 S.W.2d 643, 645 (Tex. 1995)(affidavit not defective where affiant swore before officer authorized to administer oaths that facts attested to were based on personal knowledge; in absence of challenge to authenticity of affidavit, submission of a copy provides no ground for rejection); Dolcefino v. Randolph, 19 S.W.3d 906, 927 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2000, pet. denied)(trial court may not consider hearsay evidence in ruling on motion for summary judgment). When an affidavit suffers from a mere formal defect in form, a party must object to the formal defect and secure a ruling from the trial court to preserve error. TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(f); see Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166, citing Well Sols., Inc., 32 S.W.3d at 317. Defects that are purely formal may not be raised for the first time on appeal. Well Sols., Inc. v. Stafford, 32 S.W.3d 313, 317 (Tex.App.-San Antonio 2000, no pet.). Conversely, a party may first complain on appeal about a purely substantive defect present in an affidavit. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166, citing Well Sols., Inc., 32 S.W.3d at 317; Dailey v. Albertson's, Inc., 83 S.W.3d 222, 225 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2002, no pet.). Unless an order sustaining the objection to summary-judgment evidence is reduced to writing, signed, and entered of record, the evidence remains part of the summary-judgment proof even if a party has objected to an opponent's summary-judgment evidence. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166, citing Mitchell v. Baylor Univ. Med. Ctr., 109 S.W.3d 838, 842 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2003, no pet.).

Analysis

Houle asserts that he specifically objected in the trial court to information missing from Diana Trittipoe's affidavit when he observed that the affidavit "does not advise the court as to how [Trittipoe] comes by that `personal knowledge.'" Houle also candidly acknowledges that the trial court "did not comment on the objection." Capital One counters that Houle not only failed to secure the trial court's ruling on this specific objection but also failed to obtain the trial court's ruling regarding his objection that Trittipoe failed to address the redaction of information in account statements which she averred in her affidavit to be true and correct copies of original documents. For these reasons, Capital One contends Houle has failed to preserve for our review his trial court objections to Capital One's summary judgment evidence. In reply, Houle asserts that because the business records failed to satisfy the standard for summary judgment on the bases that they were not properly authenticated, were incomplete, and contained conflicting inconsistencies, "an actual objection was not necessary to preserve error."

The record before us does not include a reporter's record of any proceedings in the trial court nor does it contain an express ruling by the trial court on Houle's objections to Capital One's summary-judgment evidence. The trial court's final summary judgment does include a Mother Hubbard clause that declares "[a]ll relief not expressly granted is denied." We look to Houle's response to Capital One's motion for summary judgment to determine whether Houle preserved error.

Conflicting Inconsistencies

On appeal, Houle complains in part that the business records used to support the summary judgment "contained conflicting inconsistencies." Houle's brief includes a heading titled, "Inconsistent Records," in which he notes that the Capital One records attached to Trittipoe's affidavit are missing a record for July 2010, reflect an increased interest rate, and despite being declared true and correct copies, have had the account number redacted. Unlike his appellate complaint, in his response to Capital One's motion for summary judgment, Houle did not globally complain that the business records contain "conflicting inconsistencies." To the extent that Houle's "conflicting inconsistencies" complaint may be deemed to stand independently of the complaints set out under the "Inconsistent Records" portion of his brief, we find it is not preserved for our consideration. TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1.

Defects of Form

In his response to the summary-judgment motion, Houle specifically complained in the trial court:

Diana Trittipoe is not an employee of the Plaintiff, nor is she the custodian of records for the Plaintiff. She is an employee of another company and simply claims to have `personal knowledge of the manner and method by which Capital One created and maintains certain business book and record, including computer records of customer accounts.' She does not advise the court as to how she comes by that `personal knowledge.' The Court should be suspicious of her affidavit because she claims: `The attached records are the originals or exact duplicates of the originals.' She identifies the account as consisting of 16 `Xs.' According to the Defendant's Affidavit, his account number did not consist of 16 `Xs' but contained a series of arabic numerals. It is apparent from examining the documents attached as Plaintiff's Exhibit A-1 that information has been redacted from the original document and that these copies are not `exact duplicates' which is the express language of Rule 902 (10), Texas Rules of Evidence for authentication by affidavit. The information set forth in the paragraph above has already noted that the records are not complete, and now there are not the originals or exact duplicates. The summary judgment evidence produced by Plaintiff will not support a summary judgment.

On appeal, Houle complains that the records attached to Trittipoe's affidavit were not properly authenticated, were incomplete, and were not true and complete copies of the originals because they bore redaction of Houle's specific account number with Capital One.

These purported defects are purely formal. See Well Sols., Inc. v. Stafford, 32 S.W.3d 313, 317 (Tex.App.-San Antonio 2000, no pet.)(objection to deposition or affidavit, that is, statement in writing of a fact or facts signed by party making statement, sworn to before officer authorized to administer oaths, and officially certified to by officer under his seal of office, on basis that statement does not establish foundation for statement is purely formal defect), citing Leggat, 904 S.W.2d at 645-46. Because Houle failed to object to the purported formal defects and secure a ruling from the trial court in order to preserve error, he may not raise these complaints for the first time on appeal. TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(f); see Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166, citing Well Sols., Inc., 32 S.W.3d at 317.

Although the Texas Supreme Court has recognized that an implicit ruling may be sufficient to preserve an issue for appellate review, it has clarified that the trial court's ruling must be clearly implied by the record. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166,citing In the Interest of Z.L.T., J.K.H.T., and Z.N.T., 124 S.W.3d 163, 165 (Tex. 2003). In Seim, the Court acknowledged the correct reasoning of the San Antonio Court of Appeals in Well Sols., Inc. v. Stafford, 32 S.W.3d 313, 317 (Tex.App.-San Antonio 2000, no pet.) when that court declared:

[R]ulings on a motion for summary judgment and objections to summary judgment evidence are not alternatives; nor are they concomitants. Neither implies a ruling—or any particular ruling—on the other. In short, a trial court's ruling on an objection to summary judgment evidence is not implicit in its ruling on the motion for summary judgment; a ruling on the objection is simply not `capable of being understood' from the ruling on the motion for summary judgment.

We agree that a trial court's ruling on an objection to summary judgment evidence is not implicit in its ruling on the motion for summary judgment. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166, citing Well Sols., Inc., 32 S.W.3d at 317. Moreover, that the trial court's judgment in this case includes a Mother Hubbard clause stating that "[a]ll other relief not expressly granted is denied[,]" does not constitute a showing that the trial court ruled on Houle's objections to Capital One's summary judgment evidence. See Lissiak v. SW Loan OO, L.P., 499 S.W.3d 481, 488 (Tex.App.-Tyler 2016, no pet.).

We conclude the trial court did not implicitly rule on Houle's objections to Capital One's summary-judgment evidence. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166. As these complaints have not been preserved, they are waived. TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1.

We conclude the trial court did not implicitly rule on Houle's objections to Capital One's summary-judgment evidence. See Seim, 551 S.W.3d at 166. As these complaints have not been preserved, they are waived. TEX.R.APP.P. 33.1.

Personal Knowledge

Affidavits supporting a summary-judgment motion must be made on personal knowledge, not supposition, and "shall set forth such facts as would be admissible in evidence, and shall show affirmatively that the affiant is competent to testify to the matters stated therein." TEX.R.CIV.P. 166a(f); TEX.R.EVID. 602 ("A witness may testify to a matter only if . . . the witness has personal knowledge of the matter."); Marks v. St. Luke's Episcopal Hosp., 319 S.W.3d 658, 666 (Tex. 2010). An affidavit not based on personal knowledge is not legally sufficient. Id., 319 S.W.3d at 666, citing Kerlin v. Arias, 274 S.W.3d 666, 668 (Tex. 2008)(per curiam).

Houle contends on appeal as he did in the trial court that Trittipoe failed to demonstrate adequate personal knowledge underlying her testimony for proving up the attached Capital One business records. We have previously held that a lack of personal knowledge, reflected in the affiant's testimony itself and not just as the lack of a formal recitation, is a defect of substance that may be raised for the first time on appeal. Dailey v. Albertson's, Inc., 83 S.W.3d 222, 226 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2002, no pet.).

To the extent Houle's complaint may be said to constitute a defect of substance and may be raised for the first time on appeal, we conclude it is without merit. The essence of his complaint is that there is some reason to doubt whether Trittipoe's testimony regarding Capital One's record-keeping procedures was based on her personal knowledge because she is employed by a Capital One agent and affiliate rather than Capital One itself.

Trittipoe adequately demonstrates her competence to give the testimony she provided. She testified that her responsibilities as a Litigation Support Representative provide her access to all relevant systems and documents needed to validate the information she has supplied. Trittipoe also explained that her personal knowledge of the manner and method by which Capital One creates and maintains certain books and records, including computer records of customer accounts, arises from the scope of her responsibilities as a Litigation Support Representative. In that role, Trittipoe also declared that records of Houle's credit card account ending in "XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX" were kept in the regular course of its business and that the account is the subject of this suit.

The records are comprised of over 180 pages of documents that Trittipoe identifies as related to Houle's account with Capital One. Trittipoe identified the records as originals or exact duplicates of the originals and established them to be Capital One's business records containing statements of activity on Houle's account. The records reflect extensions of credit requested by Houle and extended by Capital One, payments made by Houle and other credits, fees and interest assessed on the account, installments due and owing, and account balances owed. Trittipoe explained that the records contain the terms and conditions applicable to Houle's account, and also include the application Houle signed as well as copies of Houle's payments on the account. Trittipoe concludes her affidavit by stating, "As of the date of this affidavit, the amount due and owing on the account is $4,007.72."

Contrary to Houle's suggestion, the rules of evidence do not require that the qualified witness who lays the predicate for the admission of business records be their creator or have personal knowledge of the contents of the record. SeeTEX.R.EVID. 803(6), 902(10)[1]; see also Bridges v. Citibank (S.D.) N.A., No. 02-06-00081-CV, 2006 WL 3751404, at *2 (Tex.App.-Fort Worth Dec. 21, 2006, no pet.)(mem.op.), citing In re K.C.P., 142 S.W.3d. 574, 578 (Tex.App.-Texarkana 2004, no pet.). The witness is required only to have personal knowledge of the manner in which the records were kept. See TEX.R.EVID. 803(6), 902(10); see also Bridges, 2006 WL 3751404, at *2.

We conclude that Trittipoe's testimony adequately demonstrates the basis for her personal knowledge of the manner and method by which Capital One kept its records and the other facts to which she testified. Other Texas courts have considered similar affidavit testimony by such personnel as adequate to establish the basis for the affiants' personal knowledge and competence. See, e.g., Damron v. Citibank (S. Dakota) N.A., 03-09-00438-CV, 2010 WL 3377777, at *3-4 (Tex.App.-Austin Aug. 25, 2010, pet. denied)(mem. op.); McFarland v. Citibank (S. Dakota), N.A., 293 S.W.3d 759, 762 (Tex.App.-Waco 2009, no pet.)(affiant's affidavit based on personal knowledge derived from her work as a litigation analyst was not conclusory as it provided proper basis for admitting business records); Wynne v. Citibank (S.D.) N.A., No. 07-06-000162-CV, 2008 WL 1848286, at *2 (Tex.App.-Amarillo Apr. 25, 2008, pet. denied)(mem.op.); Jones v. Citibank (S.D.), N.A., 235 S.W.3d 333, 337 (Tex.App.-Fort Worth 2007, no pet.); Hay v. Citibank (S.D.) N.A., No. 14-04-01131-CV, 2006 WL 2620089, at *3 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] Sept. 14, 2006, no pet.)(substitute op.).

Genuine Issue of Material Fact

The four elements of a breach of contract claim are: (1) the existence of a valid contract; (2) performance, or tendered performance, by the plaintiff; (3) breach of the contract by the defendant; and (4) damages to the plaintiff resulting from that breach. Restrepo v. All. Riggers & Constructors, Ltd., 538 S.W.3d 724, 740 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2017, no pet.), citing Velvet Snout, LLC v. Sharp, 441 S.W.3d 448, 451 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2014, no pet.). A party is entitled to relief for a stated account where: (1) transactions between the parties give rise to indebtedness of one to the other; (2) an agreement, express or implied, between the parties fixes an amount due, and (3) the one to be charged makes a promise, express or implied, to pay the indebtedness. Eaves v. Unifund CCR Partners, 301 S.W.3d 402, 407-08 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2009, no pet.); McFarland v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., 293 S.W.3d 759, 763 (Tex.App.-Waco 2009, no pet.); Dulong v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., 261 S.W.3d 890, 893 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2008, no pet.). Because an agreement on which an account stated claim is based can be express or implied, a creditor need not produce a written contract to establish the agreement between the parties; an implied agreement can arise from the acts and conduct of the parties. See Walker v. Citibank, N.A., 458 S.W.3d 689, 692-93 (Tex.App.-Eastland 2015, no pet.), citing McFarland, 293 S.W.3d at 763.

In response to Capital One's motion for summary judgment, Houle filed an affidavit in which he complained that Capital One's documents were not original or exact duplicates of account statements he had received, and noted both that his statements did not contain solid black lines and his account number had numeric digits rather than the "Xs" contained in Capital One's summary judgment evidence. Houle acknowledged that although he had disputes with Capital One regarding charges and credits to his account, Capital One later credited payment and refunded a late penalty. Houle also complained that Capital One had increased its interest rate in an arbitrary manner, specifically in July 2010 when he made a payment and Capital One purportedly doubled the "interest rate," and without specifying, he asserted in a conclusory manner that the account is not true and correct and that he does not owe the amount Capital One claims is due. There is no evidence in the record from Houle or Capital One regarding payments made in July 2010.

The evidence showed that Capital One and Houle entered into a credit card agreement, that Capital One issued a credit card to Houle, that Houle used the credit card to make purchases, and that Houle made payments on the account. Evidence of the card-member agreement was presented to the trial court through Trittipoe's affidavit. The agreement provides that Capital One would allow Houle to purchase goods and services with credit in exchange for payment. According to the terms of the agreement, Capital One would assess interest charges based on the application of the annual percentage rate, which varies as the index for the rate increases or decreases, and in the event of two late payments, the variable annual percentage rate would increase to an unspecified "penalty annual percentage rate." The June 2010 statement having a July 2010 due date shows an annual percentage rate of 13.52%. Further, the record showed that Houle's account was past due for six consecutive months, from January 2013-June 2013, with an annual percentage rate of 29.40%, incurred past due and over limit fees, and was thereafter "charged off," with a final balance of $4007.72.

Based on the card-member agreement, Capital One's extension of credit on Houle's account, Houle's usage of the credit card and failure to pay on the account in accordance with the terms of the agreement, and Capital One's resulting damages, we conclude that Capital One satisfied each element of its breach of contract cause of action and, if necessary for the account-stated cause of action, conclude or reasonably infer that Houle agreed to pay a fixed amount equal to the purchases and cash advances he made, plus interest. See Dulong, 261 S.W.3d at 894; McFarland, 293 S.W.3d at 763-64 (cases holding creditor could collect debt on account stated where, based on series of transactions reflected on account statements, creditor established that card holder agreed to full amount shown on statements and impliedly promised to pay indebtedness). We conclude that no genuine issue of material fact exists as a matter of law as to any element of Capital One's causes of action against Houle. Taking Houle's affidavit as true, and indulging every reasonable inference and resolving any doubts in his favor, we conclude that Houle failed to satisfy his burden of presenting evidence that raises a genuine issue of material fact. See Nixon, 690 S.W.2d at 548-49.

Moreover, with limited exceptions, Rule 21c requires that unless the inclusion of sensitive data is required by statute, court rule, or administrative regulation, a document containing sensitive data, including credit card numbers, may not be filed with the court unless that data is redacted. See TEX.R.CIV.P. 21c(a)(2), (b). The rule requires that sensitive data be redacted by using the letter "X" in place of each omitted digit or character or by other means specified therein. SeeTEX.R.CIV.P. 21c(c). The redaction of Houle's credit cards account data from the records attached to Trittipoe's affidavit in compliance with Rule 21c does not raise a genuine issue of material fact as to any element of Capital One's breach of contract and account stated claims.

The trial court did not err in granting summary judgment in favor of Capital One. Houle's sole issue on appeal is overruled.

CONCLUSION

The trial court's judgment is affirmed.

[1] Rule 902(10)(b) sets out a form affidavit to be used when introducing business records under Rule 803(6). TEX.R.EVID. 902(10)(b), 803(6). Rule 902(10)(b) provides, however, that the form set out in the rule is not exclusive. An affidavit that substantially complies with the affidavit set out in the rule will suffice. TEX.R.EVID. 902(10)(b); see also Fullick v. City of Baytown, 820 S.W.2d 943, 944 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 1991, no writ).

No comments:

Post a Comment