Show me the Promissory Note that Saliha Madden made to Bank of America, and show me the Valid-when-made Doctrine.

Madden v Midland Funding, LLC, 786 F.3d 246 (2d Cir. 2015), cert. denied, 136, S. Ct. 2505 (2016).

Today’s post will discuss a scholarly piece that advocates

the opposite: the containment of Madden

and how to prevent the spread of the infection to the jurisprudence of other

circuits.

CURIOSITY WITH OR WITHOUT PROBABLE CAUSE?

The article, penned by lawyers at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius

LLP, finds it curious that the courts in Madden didn’t resurrect and apply the VALID-WHEN-MADE

doctrine, which even the authors admit has a scant grounding in recent

caselaw.

But there is a fix. And it does not even require Congress to

legislate one. Here it is, violà: The valid-when-made doctrine has been so

omnipresent all along that it did not need overt acknowledgment. Hence the

dearth of published authority. It’s been lingering in the collective consciousness of the industry for at least a century. All too well understood by those in the

know. If only the courts proclaimed so, now that the industry has found it

necessary to bring it up, beleaguered and under the threat of impending

collapse.

CONTAINING THE SPREAD OF MADDEN BEYOND MIDLAND

The lawyer-led line of argument culminates in blaming other

lawyers, Midland’s lawyers, for losing the case on account of lousy briefing.

It purports to offer sage advice to financial industry peers on how to improve

their game so as to make sure that other Circuits don’t catch the Madden infection.

Curious indeed.

Since the article blames Midland’s lawyers for their subpar

performance (without naming them, of course (see Google Scholar version of the Madden opinion, if interested

in their identity), and since it unabashedly promotes the vested interests of

the banks and financial industry in maximizing extraction of money at high

rates of interest from people that have fallen on hard times and cannot pay

their debts, it seems only appropriate – in the interest of fairness and

balance – to subject this industry advocacy masterpiece of legal scholarship to

a no-holds-barred -- or at least rigorous - critical analysis as to soundness of reasoning and evidentary support.

GETTING THE FACTS WRONG AB

INITIO

By way of first salvo, the Curious authors get the facts wrong about

the case, and not exactly on a nontrivial matter.

The account at issue in Madden

v Midland involved an open-end credit card plan (aka credit card account)

and the account was not sold by Bank of America to an unaffiliated national bank, contrary representation by the Curious authors notwithstanding. The

account ended up being owned by FIA Card Services, a wholly owned subsidiary of

Bank of America Corporation, and the transfer transaction was in the nature of

a merger, not an asset sale to a third-party national bank.

While the sale to Midland

Funding, LLC was an asset sale (portfolio sale), the transfer of the credit card account to FIA was not, at least not to an unrelated third-party. In fact, FIA was created by Bank of America (holding company) to consolidate its

credit card operations in a Delaware-located national bank. Presumably to take

advantage of the usury-friendly regulatory climate there. Or credit-access

friendly, as the industry would have the gullible press and public believe.

|

| BANK OF AMERICA - FIA CARD SERVICES N.A. MERGER HISTORY |

From OCC's 2010 Evaluation of FIA Card Services N.A.

under the Community Reinvestment Act

|

| Exemplar of Bank of America N.A.(USA) Cardmember Agreement (C 2008) with Arizona choice-of-law clause (see highlight in 2nd column) |

If a presumably vetted scholarly article cannot even get

facts straight that are a matter of public record, it sheds doubt on whether it

should even have been published. And any conclusions drawn from an argumentation

that is predicated on false factual premises should not only be taken with a

grain of salt or two, but should be deemed dubious at best, if not outright unworthy

of serious consideration until the factual premises are corrected and accurately stated.

THE JOURNEY OF MADDEN’S CREDIT CARD DEBT

The bone of contention in Madden centered on what happens when a debt is transferred from a

national bank to a nonbank, in that case Midland Funding LLC, a debt buyer.

Even if the error regarding the ownership history of the account prior to

charge-off and sale to Midland Funding is not relevant in the narrow issue of federal

preemption in the case (more on that later), there is a second fundamental flaw

that the Curious authors fudge in

inexcusable fashion even though they otherwise offer very astute observations: it

involves the distinction between notes and closed-end credit as one category,

and open-end credit on the other.

As the PR-amenable moniker implies, the VALID-WHEN-MADE

doctrine is all about the validity of a loan contract at the point of

origination. That presumes that the debt subject to transfer does, in fact,

stem from a loan, and that the loan contract or a note is actually executed on

a definite date at a definite place. Or, alternatively, that a loan was made as a factual matter, since the "making" in the "when-made" component could either refer to executing a promissory as "maker" (action by the borrower) or "making" the loan by disbursing funds pursuant to a loan agreement (action by the lender, or by a disbursement agent, in the rent-a-charter scenario).

But the debt in Madden

neither involved a promissory note (never mind a negotiable one), nor even a signed loan contract in any other shape or form. The vast majority of credit card accounts do not involve signed contracts and debt incurred such an account cannot be characterized as “a loan” (singular) because such accounts involve repeat

transactions, or at least allows for them. The account at issue in Madden was an open-end extension of credit

governed by Delaware law. It would, of course, be based on a written

“agreement” because TILA requires cost-of-credit terms to be in writing, and

because Delaware banking law requires a written agreement for open-end credit plans,

but the terms of that agreement would only become a contract, and give rise to

an obligation to repay debt, upon use of the credit card or some other manner

of credit utilization, such as a cash withdrawal, charge authorization that

does not involve use of the card, or use of a check drawn on the credit account.

The implications of this are rather obvious. Assuming the

valid-when-made theory even applies, it would kick in each time a charge

authorization is made, not just at the point in time when the account is opened,

and not just the first time the issued card is used to make a purchase and

thereby cause a debit to the account.

A CREDIT CARD ACCOUNT IS NOT A PROMISSORY NOTE AND IS NOT TRANSFERRED BY NEGOTIATION, BUT IN BULK BY BILL OF SALE

Assuming, for starters, that the valid-when-made proposition

makes any sense at all in this context, it would have to be applied iteratively

to each instance of card utilization and “freeze” the interest rate in effect

at that time of the transactions under the “when made” element. But this cannot

be done after as little as a single billing cycle because it is in the nature

of most credit card schemes to add the charges associated with new transactions

to the revolving balance, if any, and to subject the aggregate balance to the

applicable interest rate then in effect (in the vast majority of accounts, a

variable APR or its daily equivalent). This makes it well-neigh impossible to apply

the valid-when-made concept to any particular component of the revolving

balance except when a single transaction, such as a promotional cash advance

made by means of a check, is tracked separately in the accounting system (and

periodic billing statements), i.e. as a distinct balance type to which a

special interest rate is applied.

Industry advocates might argue that the valid-when-made

“principle” should be applied to the charge-off balance and the interest rate

then in effect. Conceptually, this proposition violates logic because a loan is

obviously not “made” when the borrower has already been in default for 180 days,

which is the ordinary period of time before the account balance is charged off.

As a practical matter, of course,

the industry could simply take the position that whatever the interest rate was

at that time of charge-off (which is a definite point in time) should be the

interest rate that the national bank should be able to bequeath to the

purchaser on occasion of the subsequent portfolio sale. In a similar vein, they

might argue that the national bank should be able to “freeze” the interest rate

too, in cases where the default rate is a variable APR based on prime.

Converting a variable APR to a

fixed APR would simplify matters for the purchaser because the latter would not

have to track changes in prime and recalculate the charge-off balance

accordingly. The same advantage would hold true if the debt buyer were to

calculate additional interest separately as TSI does in National Collegiate

Student Loan Trust collection cases, albeit based on LIBOR, rather than U.S.

Prime Rate. See exemplar of a standard Exhibit E from TSI below:

Because a fixed APR would

simplify the accounting and reduce the overhead for the purchaser, it might enhance,

at least slightly, the price the seller can command for the portfolio. The

bank, as seller, would thus have an incentive to raise the APR to the highest

rate, and then freeze it at that rate (as a static rate, rather than a variable

one) before disposing of the account as a bad debt.

Obviously, the rate in effect at the time of charge-off

would not be the rate that was in effect at the time the credit card account

was opened or when the charges resulting in the debt were incurred (“when made”). It would predictably be higher because it is standard

industry practice to apply a higher default interest rate, or penalty rate, to

delinquent accounts.

The rate at the time of the portfolio sale to the non-bank

entity would be the rate on the last account statement, or its electronic

equivalent. Simple enough. But is that even a valid contract rate amenable to

being bequeathed to a successor-in-interest?

WHERE IS THE AGREEMENT ON THE DEFAULT RATE?

The valid-when-made “doctrine” advocated by the financial

industry post-Madden -- whether

contrived, discovered, or merely resurrected (a topic for future exploration) -- not only assumes a definite point in time when the loan contract as “made”, it

also assumes that the interest rate was fixed at that time (fixed APR or margin plus Prime), and that such rate

is evidenced by the written instrument, whether a promissory note or a loan

contract.

Again, this assumption does not hold in the case of credit

card accounts because there is typically no written and signed contract at all.

And the initial TIL disclosures are just that: initial.

The interest rate and the other cost-of-credit terms are subject

to unilateral amendment by the credit card issuer. How this is done may vary

somewhat among the states that major card issuers call home (Delaware,

South Dakota, North Carolina, Utah, Virginia), and is also regulated by the TILA, but the

basic business model, and the chosen jurisdiction’s law, allows the card

issuing bank to raise the interest rate to whatever is within the law in its

home state, and the cardholder can then either suck it up or close the account

and pay off the balance on the existing terms, assuming proper prior notice and

grace period (at least post-Crash under the Card Act). The account in Madden is a rather old one, so it is not so clear which version of the TILA-required disclosures applied.

When the cardholder resorts to self-help and stops making

payments, the creditor will likely raise the rate to the default rate, which

will likely be even higher than the rate “proposed” in the

notice-of-change-in-terms notice.

If that rate then -- by operation of the bank’s automated accounting

system -- ends up being 27.24%, can that rate be said to be the rate at inception ("when made")? Obviously not. It is the rate the bank applies at the back

end, not the front end.

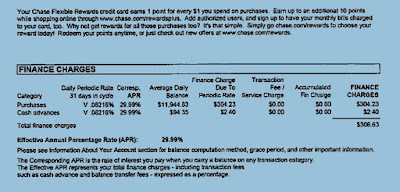

|

| Exemplar of CHASE card statement for delinquent account reflecting 27.24% APR and monthly late of fee of $39.00 (from a Midland Funding collection suit in Texas) |

|

| Exemplar of even higher rate of 29.99% APR on delinquent Chase credit card account from 2011 Midland Funding collection suit in Texas |

And since the cardmember would not have consented to

this highest-ever rate on his or her account by using the card (the account

was, after all, already closed), he or she did not consent to it. At least not

that way, i.e. by continued use of the account to make purchases as a

manifestation of assent to the more expensive terms without a signature on a

written amendment to the contract.

That leaves the argument that the cardholder consented to

the 27.24% rate (or even higher) when she or he agreed to the standard terms of the account,

which probably contain a provision stating what the penalty rate is, or a

formula by which the delinquency rate is calculated (typically a higher margin

percentage over Prime). -- But where is that agreement?

When American Express sues on delinquent accounts, it

typically produces an account-specific Cardmember Agreement that is dated,

contains the name of the cardholder, the type of card/account, and the ending

digits of the credit card number. It also shows the account-specific interest rate(s) and

other terms on Part 1 of 2.

But that has not been so for the vast majority of the FIA/Bank of

America accounts, at least not those that ended up in litigation in Texas courts, not to mention cases brought by debt buyers.

Even in cases in which FIA itself appeared as Plaintiff, it would

typically attach a generic

cardmember agreement that was not expressly linked to the account, sometimes

from Bank of America (USA) N.A. (Arizona) rather than Bank of America, N.A. or

from FIA Card Services, N.A., or it would produce multiple generic cardmember

agreements or a combination of cardmember agreement and change-in-terms

notices.

Only recently has FIA's successor, BANA, started to support motions for summary judgment in collection suits with copies of cardmember agreements and subsequent change-of-terms notices with cardholder's name printed on them. See examples of penalty APR and late fee amendments below (names cropped).

Generic cardmember agreements typically do no even contain the account-specific cost-of-credit terms that are printed on separate TIL disclosures statements called Schedule or Rate Table, or some similar label, depending on card issuer.

Only recently has FIA's successor, BANA, started to support motions for summary judgment in collection suits with copies of cardmember agreements and subsequent change-of-terms notices with cardholder's name printed on them. See examples of penalty APR and late fee amendments below (names cropped).

Exemplars of change-in-terms notices regarding late fee (above)

and penalty APR (below)

Generic cardmember agreements typically do no even contain the account-specific cost-of-credit terms that are printed on separate TIL disclosures statements called Schedule or Rate Table, or some similar label, depending on card issuer.

All of which makes it hard to determine -- even in the

context of contested cases that allow for resort to discovery and force the

Plaintiff to prove its case with summary judgment evidence or business records

affidavit (rather than getting judgments by default) --- what cardmember

agreement governs the claim asserted in litigation, not to mention what

interest rates. The interest rates may, of course, have changed, not merely

because they are often pegged to the prime rate, but because the issuing bank

has exercised it right to unilaterally raise the rate, subject to tacit

approval by the cardholder in the form of continued use of the credit card, as

opposed to the cardholder closing the account and paying the balance off under

the then-existing rates.

Industry advocates raise the specter of upsetting financial

market by “uncertainty” as the whether a debt-buyer such as Midland Funding,

LLC can assess post-chargeoff interest at the same rate as the original

creditor. They are not engaging in overkill. They are shooting at a phantom.

Even when card issuers sue on their own accounts (rather

than selling them to outfits such as Midland Funding, CACH, LLC, Credigy Receivables, Crown Asset Management, LVNV Funding LLC, Portfolio Recovery Associates LLC, Troy Capital LLC, etc.), they often

do not produce complete documentation of what the contracted-for interested

rate actually is, and the difference between charge-off balance with and

without post-charge-off interest would not be very large in any event as long

as the banks sue promptly, which nowadays they typically do. For a reason.

People who default on a credit card often default on several. So the creditor that sues first is first in line to collect with the aid of the courts and their

power to enforce judgments coercively. American Express is known to file suit promptly and produces account-specific Cardmember Agreements. BANA now appears to be following this model. To the extent other national banks go that route, the issue of whether debt buyers can enforce the terminal interest rate on charged-off accounts becomes altogether moot.

DEBT BUYER MIDLAND AND ITS COLLECTOR HAVE A BIG STAKE IN THE OUTCOME IN MADDEN, NATIONAL

BANKS DO NOT

Midland’s bottom line is obviously affected, and the fact

that Madden brought an FDCPA-based class action, rather than merely defending

against post-charge-off interest as uncollectible in the context of a debt

collection suit, gave Midland plenty of reason to put up a good fight all the

way to the Supreme Court.

To apply NBA preemption to an action taken by a non-national bank entity, application of state law to that action must significantly interfere with a national bank's ability to exercise its power under the NBA. See Barnett Bank of Marion Cnty., N.A. v. Nelson, 517 U.S. 25, 33, 116 S.Ct. 1103, 134 L.Ed.2d 237 (1996); Pac. Capital Bank, 542 F.3d at 353.

But the impact on the original creditors is minimal, and

cannot possibly substantially interfere with their ability to extract the

highest interest rate the market (i.e. the cardholders) will bear, i.e. their

much-touted powers under the National Bank Act to force their customers in other

states to pay the high rate of interest that is lawful in the state where

they set up shop. And the big U.S. bank holding companies do have that choice. They can relocate their credit card subsidiary to Delaware or South Dakota.

Why minimal? -- Because debt buyers such as Midland acquire the charged-off accounts at a very

small fraction of the nominal balance, and that balance is itself already

artificially inflated because it will generally include 6 months of interest at

the highest possible rate (default/penalty rate) plus monthly late fees,

neither of which the bank had any realistic expectation to collect. The

interest was merely accrued on the books, and represents “phantom” earnings on

uncollectible indebtedness. In effect, the additional interest assessed after

default is not even a loss. The loss occurred when the debtor stopped making

payments, and the bank stopped any further losses by cutting off the cardholder’s

charging privileges. The accrual of "phantom" interest at high rates merely increased the charge-off balance and the associated tax benefits of writing it off as a bad debt.

|

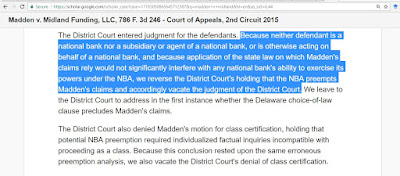

| The Second Circuit's key holding in Madden v. Midland Funding |

NATIONAL BANKS CAN AND DO AVOID THE ADVERSE IMPACT FROM

MADDEN, IF ANY, AND HAVE BEEN DOING SO EVEN BEFORE MADDEN

WAS DECIDED

Even if there a non-trivial marginal impact in the form of a

lower sale price of an already very low price realized in the (teritiary) debt

buying markets for portfolios of unsecured charged-off consumer debt, national

banks could avoid this effect by filing collection suits in their own names.

Citibank, N.A. (and previously, Citibank (South Dakota) N.A.), have done that

for years; American Express Bank, FSB, has done it for years; American Express

Centurion Bank (a Utah industrial bank) has done it for years.

Bank of America, N.A. and – prior to that – FIA Card

Services, N.A. – has also been filing credit card debt collection cases in its own name for

years. That includes years prior to Madden

and thus years prior to the doom and gloom propagated by the industry in Madden’s wake.

Where is the harm?

The latest installment in the campaign to promote the Valid-when-made "doctrine" to counter Madden still fails to show any.

MADDEN IS MARGINAL BECAUSE THE MARKET VALUE OF CHARGED-OFF

CREDIT ACCOUNTS IS CLOSE TO DE MINIMIS

Madden does not stand for the proposition that loans

originated by national banks that are not in default at the time of the

transfer or securitization is not imbued with preemption protection. It is

limited to charged-off accounts, which were worth no more than pennies on the

dollar at that point, as reflected in the portfolio sale price. No big liquidity

boost there, thanks to the off-loading. Not much in the way of capital

recovery. The rationale for charge-off is, after all, the nonperformance of the

loan in question. Sale of debt deemed uncollectible does not do much for the

liquidity cycle.

And the interest charges complained of by Madden were the post-chargeoff interest

charges assessed by Midland at the national bank’s default rate, rather than

interest assessed by FIA or Bank of American that became part of the charge-off

balance that Midland acquired.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ("OCC"), "a federal agency that charters, regulates, and supervises all national banks," Town of Babylon v. Fed. Hous. Fin. Agency, 699 F.3d 221, 224 n. 2 (2d Cir.2012), has made clear that third-party debt buyers are distinct from agents or subsidiaries of a national bank, see OCC Bulletin 2014-37, Risk Management Guidance (Aug. 4, 2014), available at http:// www.occ.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2014/bulletin-2014-37.html

Finally, the case brought against Midland was a fair debt collection case. Midland had much as stake because it was brought as a class action on behalf of a class consisting of debtors of 49,780 accounts to which Midland Credit Management, Inc. had sent dunning letters asserting the disputed post-chargeoff interest rate.

National Banks are not even covered by the FDCPA. If they were adversely affected as a result of Midland and other debt buyers running afoul of fair debt collection laws in New York -- as the industry unconvincingly claims -- they could easily adjust by opting not to sell portfolios of New York accounts to debt buyers, and hire a law firm to do it in their own name instead.

National Banks are not even covered by the FDCPA. If they were adversely affected as a result of Midland and other debt buyers running afoul of fair debt collection laws in New York -- as the industry unconvincingly claims -- they could easily adjust by opting not to sell portfolios of New York accounts to debt buyers, and hire a law firm to do it in their own name instead.

That is what many credit card issuers have been doing in

Texas in the regular course of business for years, among them, as mentioned,

American Express (both banks), Citibank, N.A., Capital One, Discover, Wells

Fargo, and last but not least, Bank of America.

Madden set off

much hype and hyperventilation. It has not made the heavens fall. Nor should it

make much rain, contrary hopes notwithstanding.

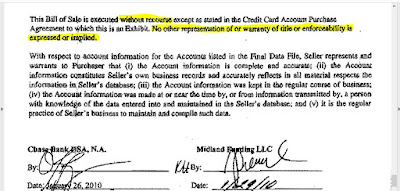

THE ARGUMENT REGARDING MARKET EXPECTATIONS AS TO ENFORCEABILITY OF "THE NOTE" IS COMPLETE NONSENSE IN THIS CONTEXT - THE SELLERS SELL TO DEBT BUYERS WITHOUT RECOURSE AND WITH DISCLAIMERS OF WARRANTIES AS TO ENFORCEABILITY

THE ARGUMENT REGARDING MARKET EXPECTATIONS AS TO ENFORCEABILITY OF "THE NOTE" IS COMPLETE NONSENSE IN THIS CONTEXT - THE SELLERS SELL TO DEBT BUYERS WITHOUT RECOURSE AND WITH DISCLAIMERS OF WARRANTIES AS TO ENFORCEABILITY

Any exception to the "without recourse" nature of the sale of portfolios of bad debt by the national bank to the debt-buyer are addressed in the sale-purchase agreement, which surely also has an integration clause; hence no claim of reliance of purchaser as to "validity of debt when made."

|

| Exemplar of Bill of Sale with disclaimer of warranties as to enforceability (Chase Bank USA, N.A. to Midland Funding LLC) |

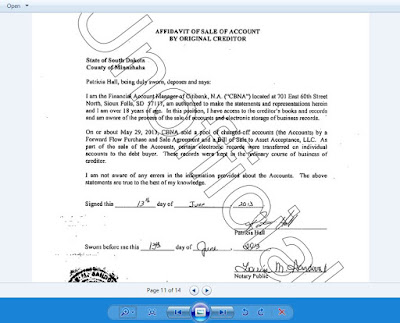

TRANSFER OF CHARGED-OFF ACCOUNTS BY BILL OF SALE

CITIBANK, N.A. TO MIDLAND FUNDING LLC

BILL OF SALE AND ASSIGNMENT (above)

and attached excerpt from portfolio data file for the specific account (below)

MIDLAND FUNDING AS ASSIGNEE #2

FROM CITIBANK TO ASSET ACCEPTANCE, LLC

TO MIDLAND FUNDING LLC

SOME SELLERS OF CHARGED-OFF CREDIT CARD ACCOUNTS

WILL EVEN DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL WARRANTIES IN THE BILL OF SALE ITSELF

ONE MORE BILL-OF-SALE DISCLAIMER:

... TO THE EXTENT SELLER OWNS THE ASSETS

ONE MORE BOFA REORGANIZATION WITH ASSOCIATED CHANGE OF CHOICE OF LAW, THIS TIME FROM DELAWARE TO NORTH CAROLINA

FROM CITIBANK TO ASSET ACCEPTANCE, LLC

TO MIDLAND FUNDING LLC

Charged-off credit card debt is sold in bulk by bill of sale under terms of forward-flow or portfolio sale-purchase agreements that sets forth the terms of the sale. Here are two bills of sale, one each of the two steps in the transfer from original creditor (CITIBANK, N.A.) to Midland Funding LLC via an intermediary debt buyer. -- A far cry from transfer of a negotiable instrument.

Exemplar of Midland Credit Management (MCM) Affidavit

Affiant Angela Miller testifies that no additional interest was added to the purchased balance.

SOME SELLERS OF CHARGED-OFF CREDIT CARD ACCOUNTS

WILL EVEN DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL WARRANTIES IN THE BILL OF SALE ITSELF

|

| BILL OF SALE AND ASSIGNMENT WITHOUT RECOURSE AND WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY US BANK, N.A. TO PRA |

|

| BILL OF SALE from Capital One Bank (USA) NA. to PRA pursuant to Forward Flow Receivables Sale Agreement (2016) |

... TO THE EXTENT SELLER OWNS THE ASSETS

|

| BILL OF SALE from Synchrony Bank to PRA with disclaimers |

ONE MORE BOFA REORGANIZATION WITH ASSOCIATED CHANGE OF CHOICE OF LAW, THIS TIME FROM DELAWARE TO NORTH CAROLINA

(effective Oct. 10, 2014).

|

| Notice of change in terms on Bank of America credit card account What law applies: North Carolina (previously Delaware). |

|

| FIA NO MORE (bank profile info from the FDIC (Bankfind search) |

|

| 2015 Beth Ammons Affidavit with merger history facts regarding FIA and BANA |

Saliha MADDEN,

on behalf of herself and all others similarly situated, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

MIDLAND FUNDING, LLC,

Midland Credit Management, Inc., Defendants-Appellees.

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.

247Daniel Adam Schlanger, Schlanger & Schlanger LLP, Pleasantville, N.Y. (Peter Thomas Lane, Schlanger & Schlanger LLP, Pleasantville, N.Y.; Owen Randolph Bragg, Horwitz, Horwitz & Associates, Chicago, IL, on the brief), for Saliha Madden.

Thomas Arthur Leghorn (Joseph L. Francoeur, on the brief), Wilson Elser Moskowitz Edelman & Dicker LLP, New York, N.Y., for Midland Funding, LLC and Midland Credit Management, Inc.

Before: LEVAL, STRAUB and DRONEY, Circuit Judges.

STRAUB, Circuit Judge:

This putative class action alleges violations of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act ("FDCPA") and New York's usury law. The proposed class representative, Saliha Madden, alleges that the defendants violated the FDCPA by charging and attempting to collect interest at a rate higher than that permitted under the law of her home state, which is New York. The defendants contend that Madden's claims fail as a matter of law for two reasons: (1) state-law usury claims and FDCPA claims predicated on state-law violations against a national bank's assignees, such as the defendants here, are preempted by the National Bank Act ("NBA"), and (2) the agreement governing Madden's debt requires the application of Delaware law, under which the interest charged is permissible.

The District Court entered judgment for the defendants. Because neither defendant is a national bank nor a subsidiary or agent of a national bank, or is otherwise acting on behalf of a national bank, and because application of the state law on which Madden's claims rely would not significantly interfere with any national bank's ability to exercise its powers under the NBA, we reverse the District Court's holding that the NBA preempts Madden's claims and accordingly vacate the judgment of the District Court. We leave to the District Court to address in the first instance whether the Delaware choice-of-law clause precludes Madden's claims.

The District Court also denied Madden's motion for class certification, holding that potential NBA preemption required individualized factual inquiries incompatible with proceeding as a class. Because this conclusion rested upon the same erroneous preemption analysis, we also vacate the District Court's denial of class certification.

BACKGROUND

A. Madden's Credit Card Debt, the Sale of Her Account, and the Defendants' Collection Efforts

In 2005, Saliha Madden, a resident of New York, opened a Bank of America ("BoA") credit card account. BoA is a national bank.[1] The account was governed 248*248 by a document she received from BoA titled "Cardholder Agreement." The following year, BoA's credit card program was consolidated into another national bank, FIA Card Services, N.A. ("FIA"). Contemporaneously with the transfer to FIA, the account's terms and conditions were amended upon receipt by Madden of a document titled "Change In Terms," which contained a Delaware choice-of-law clause.

Madden owed approximately $5,000 on her credit card account and in 2008, FIA "charged-off" her account (i.e., wrote off her debt as uncollectable). FIA then sold Madden's debt to Defendant-Appellee Midland Funding, LLC ("Midland Funding"), a debt purchaser. Midland Credit Management, Inc. ("Midland Credit"), the other defendant in this case, is an affiliate of Midland Funding that services Midland Funding's consumer debt accounts. Neither defendant is a national bank. Upon Midland Funding's acquisition of Madden's debt, neither FIA nor BoA possessed any further interest in the account.

In November 2010, Midland Credit sent Madden a letter seeking to collect payment on her debt and stating that an interest rate of 27% per year applied.

B. Procedural History

A year later, Madden filed suit against the defendants—on behalf of herself and a putative class—alleging that they had engaged in abusive and unfair debt collection practices in violation of the FDCPA, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1692e, 1692f, and had charged a usurious rate of interest in violation of New York law, N.Y. Gen. Bus. Law § 349; N.Y. Gen. Oblig. Law § 5-501; N.Y. Penal Law § 190.40 (proscribing interest from being charged at a rate exceeding 25% per year).

On September 30, 2013, the District Court denied the defendants' motion for summary judgment and Madden's motion for class certification. In ruling on the motion for summary judgment, the District Court concluded that genuine issues of material fact remained as to whether Madden had received the Cardholder Agreement and Change In Terms, and as to whether FIA had actually assigned her debt to Midland Funding. However, the court stated that if, at trial, the defendants were able to prove that Madden had received the Cardholder Agreement and Change In Terms, and that FIA had assigned her debt to Midland Funding, her claims would fail as a matter of law because the NBA would preempt any state-law usury claim against the defendants. The District Court also found that if the Cardholder Agreement and Change In Terms were binding upon Madden, any FDCPA claim of false representation or unfair practice would be defeated because the agreement permitted the interest rate applied by the defendants.

In ruling on Madden's motion for class certification, the District Court held that because "assignees are entitled to the protection of the NBA if the originating bank was entitled to the protection of the NBA... the class action device in my view is not appropriate here." App'x at 120. The District Court concluded that the proposed class failed to satisfy Rule 23(a)'s commonality and typicality requirements because "[t]he claims of each member of the class will turn on whether the class member agreed to Delaware interest rates" and "whether the class member's debt was validly assigned to the Defendants," id. at 249*249 127-28, both of which were disputed with respect to Madden. Similarly, the court held that the requirements of Rule 23(b)(2) (relief sought appropriate to class as a whole) and (b)(3) (common questions of law or fact predominate) were not satisfied "because there is no showing that the circumstances of each proposed class member are like those of Plaintiff, and because the resolution will turn on individual determinations as to cardholder agreements and assignments of debt." Id. at 128.

On May 30, 2014, the parties entered into a "Stipulation for Entry of Judgment for Defendants for Purpose of Appeal." Id. at 135. The parties stipulated that FIA had assigned Madden's account to the defendants and that Madden had received the Cardholder Agreement and Change In Terms. This stipulation disposed of the two genuine disputes of material fact identified by the District Court, and provided that "a final, appealable judgment in favor of Defendants is appropriate." Id. at 138. The District Court "so ordered" the Stipulation for Entry of Judgment.

This timely appeal followed.

DISCUSSION

The defendants contend that even if we find that Madden's claims are not preempted by the NBA, we must affirm because Delaware law—rather than New York law—applies and the interest charged by the defendants is permissible under Delaware law. Because the District Court did not reach this issue, we leave it to the District Court to address in the first instance on remand.

I. National Bank Act Preemption

The federal preemption doctrine derives from the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, which provides that "the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance" of the Constitution "shall be the supreme Law of the Land." U.S. Const. art. VI, cl. 2. According to the Supreme Court, "[t]he phrase `Laws of the United States' encompasses both federal statutes themselves and federal regulations that are properly adopted in accordance with statutory authorization." City of New York v. FCC,486 U.S. 57, 63, 108 S.Ct. 1637, 100 L.Ed.2d 48 (1988).

"Preemption can generally occur in three ways: where Congress has expressly preempted state law, where Congress has legislated so comprehensively that federal law occupies an entire field of regulation and leaves no room for state law, or where federal law conflicts with state law." Wachovia Bank, N.A. v. Burke, 414 F.3d 305, 313 (2d Cir.2005), cert. denied, 550 U.S. 913, 127 S.Ct. 2093, 167 L.Ed.2d 830 (2007). The defendants appear to suggest that this case involves "conflict preemption," which "occurs when compliance with both state and federal law is impossible, or when the state law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the 250*250 full purposes and objective of Congress." United States v. Locke, 529 U.S. 89, 109, 120 S.Ct. 1135, 146 L.Ed.2d 69 (2000) (internal quotation marks omitted).

The National Bank Act expressly permits national banks to "charge on any loan ... interest at the rate allowed by the laws of the State, Territory, or District where the bank is located." 12 U.S.C. § 85. It also "provide[s] the exclusive cause of action" for usury claims against national banks, Beneficial Nat'l Bank v. Anderson, 539 U.S. 1, 11, 123 S.Ct. 2058, 156 L.Ed.2d 1 (2003), and "therefore completely preempt[s] analogous state-law usury claims," Sullivan v. Am. Airlines, Inc., 424 F.3d 267, 275 (2d Cir.2005). Thus, there is "no such thing as a state-law claim of usury against a national bank." Beneficial Nat'l Bank, 539 U.S. at 11, 123 S.Ct. 2058; see also Pac. Capital Bank, N.A. v. Connecticut, 542 F.3d 341, 352 (2d Cir.2008) ("[A] state in which a national bank makes a loan may not permissibly require the bank to charge an interest rate lower than that allowed by its home state."). Accordingly, because FIA is incorporated in Delaware, which permits banks to charge interest rates that would be usurious under New York law, FIA's collection at those rates in New York does not violate the NBA and is not subject to New York's stricter usury laws, which the NBA preempts.

The defendants argue that, as assignees of a national bank, they too are allowed under the NBA to charge interest at the rate permitted by the state where the assignor national bank is located—here, Delaware. We disagree. In certain circumstances, NBA preemption can be extended to non-national bank entities. To apply NBA preemption to an action taken by a non-national bank entity, application of state law to that action must significantly interfere with a national bank's ability to exercise its power under the NBA. See Barnett Bank of Marion Cnty., N.A. v. Nelson, 517 U.S. 25, 33, 116 S.Ct. 1103, 134 L.Ed.2d 237 (1996); Pac. Capital Bank, 542 F.3d at 353.

The Supreme Court has suggested that that NBA preemption may extend to entities beyond a national bank itself, such as non-national banks acting as the "equivalent to national banks with respect to powers exercised under federal law." Watters v. Wachovia Bank, N.A., 550 U.S. 1, 18, 127 S.Ct. 1559, 167 L.Ed.2d 389 (2007). For example, the Supreme Court has held that operating subsidiaries of national banks may benefit from NBA preemption. Id.; see also Burke, 414 F.3d at 309 (deferring to reasonable regulation that operating subsidiaries of national banks receive the same preemptive benefit as the parent bank). This Court has also held that agents of national banks can benefit from NBA preemption. Pac. Capital Bank, 542 F.3d at 353-54 (holding that a third-party tax preparer who facilitated the processing of refund anticipation loans for a national bank was not subject to Connecticut law regulating such loans); see also SPGGC, LLC v. Ayotte, 488 F.3d 525, 532 (1st Cir.2007) ("The National Bank Act explicitly states that a national bank may use `duly authorized officers or agents' to exercise its incidental powers." (internal citation omitted)), cert. denied, 552 U.S. 1185, 128 S.Ct. 1258, 170 L.Ed.2d 68 (2008).

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ("OCC"), "a federal agency that charters, regulates, and supervises all national banks," Town of Babylon v. Fed. Hous. Fin. Agency, 699 F.3d 221, 224 n. 2 (2d Cir.2012), has made clear that third-party debt buyers are distinct from agents or subsidiaries of a national bank, see OCC Bulletin 2014-37, Risk Management Guidance (Aug. 4, 2014), available at http:// www.occ.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/ 251*251 2014/bulletin-2014-37.html ("Banks may pursue collection of delinquent accounts by (1) handling the collections internally, (2) using third parties as agents in collecting the debt, or (3) selling the debt to debt buyers for a fee."). In fact, it is precisely because national banks do not exercise control over third-party debt buyers that the OCC issued guidance regarding how national banks should manage the risk associated with selling consumer debt to third parties. See id.

In most cases in which NBA preemption has been applied to a non-national bank entity, the entity has exercised the powers of a national bank—i.e., has acted on behalf of a national bank in carrying out the national bank's business. This is not the case here. The defendants did not act on behalf of BoA or FIA in attempting to collect on Madden's debt. The defendants acted solely on their own behalves, as the owners of the debt.

No other mechanism appears on these facts by which applying state usury laws to the third-party debt buyers would significantly interfere with either national bank's ability to exercise its powers under the NBA. See Barnett Bank, 517 U.S. at 33, 116 S.Ct. 1103. Rather, such application would "limit[] only activities of the third party which are otherwise subject to state control," SPGGC, LLC v. Blumenthal, 505 F.3d 183, 191 (2d Cir.2007), and which are not protected by federal banking law or subject to OCC oversight.

We reached a similar conclusion in Blumenthal. There, a shopping mall operator, SPGGC, sold prepaid gift cards at its malls, including its malls in Connecticut. Id. at 186. Bank of America issued the cards, which looked like credit or debit cards and operated on the Visa debit card system. Id. at 186-87. The gift cards included a monthly service fee and carried a one-year expiration date. Id. at 187. The Connecticut Attorney General sued SPGGC alleging violations of Connecticut's gift card law, which prohibits the sale of gift cards subject to inactivity or dormancy fees or expiration dates. Id. at 187-88. SPGGC argued that NBA preemption precluded suit. Id. at 189.

We held that SPGGC failed to state a valid claim for preemption of Connecticut law insofar as the law prohibited SPGGC from imposing inactivity fees on consumers of its gift cards. Id. at 191. We reasoned that enforcement of the state law "does not interfere with BoA's ability to exercise its powers under the NBA and OCC regulations." Id."Rather, it affects only the conduct of SPGGC, which is neither protected under federal law nor subject to the OCC's exclusive oversight." Id.

We did find, in Blumenthal, that Connecticut's prohibition on expiration dates could interfere with national bank powers because Visa requires such cards to have expiration dates and "an outright prohibition on expiration dates could have prevented a Visa member bank (such as BoA) from acting as the issuer of the Simon Giftcard." Id. at 191. We remanded for further consideration of the issue. Here, however, state usury laws would not prevent consumer debt sales by national banks to third parties. Although it is possible that usury laws might decrease the amount a national bank could charge for its consumer debt in certain states (i.e., those with firm usury limits, like New York), such an effect would not "significantly interfere" with the exercise of a national bank power.

Furthermore, extension of NBA preemption to third-party debt collectors such as the defendants would be an overly broad application of the NBA. Although national banks' agents and subsidiaries exercise national banks' powers and receive protection under the NBA when doing so, 252*252 extending those protections to third parties would create an end-run around usury laws for non-national bank entities that are not acting on behalf of a national bank.

The defendants and the District Court rely principally on two Eighth Circuit cases in which the court held that NBA preemption precluded state-law usury claims against non-national bank entities. In Krispin v. May Department Stores, 218 F.3d 919 (8th Cir.2000),May Department Stores Company ("May Stores"), a non-national bank entity, issued credit cards to the plaintiffs. Id. at 921. By agreement, those credit card accounts were governed by Missouri law, which limits delinquency fees to $10. Id. Subsequently, May Stores notified the plaintiffs that the accounts had been assigned and transferred to May National Bank of Arizona ("May Bank"), a national bank and wholly-owned subsidiary of May Stores, and that May Bank would charge delinquency fees of up to "$15, or as allowed by law." Id. Although May Stores had transferred all authority over the terms and operations of the accounts to May Bank, it subsequently purchased May Bank's receivables and maintained a role in account collection. Id. at 923.

The plaintiffs brought suit under Missouri law against May Stores after being charged $15 delinquency fees. Id. at 922. May Stores argued that the plaintiffs' state-law claims were preempted by the NBA because the assignment and transfer of the accounts to May Bank "was fully effective to cause the bank, and not the store, to be the originator of [the plaintiffs'] accounts subsequent to that time." Id. at 923. The court agreed:

[T]he store's purchase of the bank's receivables does not diminish the fact that it is now the bank, and not the store, that issues credit, processes and services customer accounts, and sets such terms as interest and late fees. Thus, although we recognize that the NBA governs only national banks, in these circumstances we agree with the district court that it makes sense to look to the originating entity (the bank), and not the ongoing assignee (the store), in determining whether the NBA applies.

Id. at 924 (internal citation omitted).[2]

Krispin does not support finding preemption here. In Krispin, when the national bank's receivables were purchased by May Stores, the national bank retained ownership of the accounts, leading the court to conclude that "the real party in interest is the bank." Id.Unlike Krispin, neither BoA nor FIA has retained an interest in Madden's account, which further supports the conclusion that subjecting the defendants to state regulations 253*253does not prevent or significantly interfere with the exercise of BoA's or FIA's powers.

The defendants and the District Court also rely upon Phipps v. FDIC, 417 F.3d 1006 (8th Cir.2005). In that case, the plaintiffs brought an action under Missouri law to recover allegedly unlawful fees charged by a national bank on mortgage loans. The plaintiffs alleged that after charging these fees, which included a purported "finder's fee" to third-party Equity Guaranty LLC (a non-bank entity), the bank sold the loans to other defendants. The court held that the fees at issue were properly considered "interest" under the NBA and concluded that, under those circumstances, it "must look at `the originating entity (the bank), and not the ongoing assignee ... in determining whether the NBA applies.'" Id. at 1013 (quoting Krispin, 218 F.3d at 924 (alteration in original)).

Phipps is distinguishable from this case. There, the national bank was the entity that charged the interest to which the plaintiffs objected. Here, on the other hand, Madden objects only to the interest charged after her account was sold by FIA to the defendants. Furthermore, if Equity Guaranty was paid a "finder's fee," it would benefit from NBA preemption as an agent of the national bank. Indeed, Phipps recognized that "`[a] national bank may use the services of, and compensate persons not employed by, the bank for originating loans.'" Id. (quoting 12 C.F.R. § 7.1004(a)). Here, the defendants do not suggest that they have such a relationship with BoA or FIA.[3]

II. Choice of Law: Delaware vs. New York

The defendants contend that the Delaware choice-of-law provision contained in the Change In Terms precludes Madden's New York usury claims.[4] Although raised below, the District Court did not reach this issue in ruling on the defendants' motion for summary judgment.[5] Subsequently, in the Stipulation for Entry of Judgment, the parties resolved in the defendants' favor the dispute as to whether Madden was bound by the Change In Terms. The parties appear to agree that if Delaware law applies, the rate the defendants charged Madden was permissible.[6]

254*254 We do not decide the choice-of-law issue here, but instead leave it for the District Court to address in the first instance.[7]

III. Madden's Fair Debt Collection Practices Act Claim

Madden also contends that by attempting to collect interest at a rate higher than allowed by New York law, the defendants falsely represented the amount to which they were legally entitled in violation of the FDCPA, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1692e(2)(A), (5), (10), 1692f(1). The District Court denied the defendants' motion for summary judgment on this claim for two reasons. First, it held that there was a genuine dispute of material fact as to whether the defendants are assignees of FIA; if they are, it reasoned, Madden's FDCPA claim would fail because state usury laws—the alleged violation of which provide the basis for Madden's FDCPA claim—do not apply to assignees of a national bank. The parties subsequently stipulated "that FIA assigned Defendants Ms. Madden's account," App'x at 138, and the District Court, in accord with its prior ruling, entered judgment for the defendants. Because this analysis was predicated on the District Court's erroneous holding that the defendants receive the same protections under the NBA as do national banks, we find that it is equally flawed.

Second, the District Court held that if Madden received the Cardholder Agreement and Change In Terms, a fact to which the parties later stipulated, any FDCPA claim of false representation or unfair practice would fail because the agreement allowed for the interest rate applied by the defendants. This conclusion is premised on an assumption that Delaware law, rather than New York law, applies, an issue the District Court did not reach. If New York's usury law applies notwithstanding the Delaware choice-of-law clause, the defendants may have made a false representation or engaged in an unfair practice insofar as their collection letter to Madden stated that they were legally entitled to charge interest in excess of that permitted by New York law. Thus, the District Court may need to revisit this conclusion after deciding whether Delaware or New York law applies.

Because the District Court's analysis of the FDCPA claim was based on an erroneous NBA preemption finding and a premature assumption that Delaware law applies, we vacate the District Court's judgment as to this claim.

IV. Class Certification

Madden asserts her claims on behalf of herself and a class consisting of "all persons residing in New York [] who were sent a letter by Defendants attempting to collect interest in excess of 25% per annum [] regarding debts incurred for personal, family, or household purposes." Pl.'s Class Certification Mem. 1, No. 7:11-cv-08149 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 18, 2013), ECF No. 29. The defendants have represented that they sent such letters with respect to 49,780 accounts.

255*255 Madden moved for class certification before the District Court. The District Court denied the motion, holding that because "assignees are entitled to the protection of the NBA if the originating bank was entitled to the protection of the NBA... the class action device in my view is not appropriate here." App'x at 120. Because the District Court's denial of class certification was entwined with its erroneous holding that the defendants receive the same protections under the NBA as do national banks, we vacate the denial of class certification.

CONCLUSION

We REVERSE the District Court's holding as to National Bank Act preemption, VACATE the District Court's judgment and denial of class certification, and REMAND for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

[1] National banks are "corporate entities chartered not by any State, but by the Comptroller of the Currency of the U.S. Treasury." Wachovia Bank v. Schmidt, 546 U.S. 303, 306, 126 S.Ct. 941, 163 L.Ed.2d 797 (2006).

[2] We believe the District Court gave unwarranted significance to Krispin's reference to the "originating entity" in the passage quoted above. The District Court read the sentence to suggest that, once a national bank has originated a credit, the NBA and the associated rule of conflict preemption continue to apply to the credit, even if the bank has sold the credit and retains no further interest in it. The point of the Krispin holding was, however, that notwithstanding the bank's sale of its receivables to May Stores, it retained substantial interests in the credit card accounts so that application of state law to those accounts would have conflicted with the bank's powers authorized by the NBA. The crucial words of the sentence were "in these circumstances," which referred to the fact stated in the previous sentence of the bank's retention of substantial interests in the credit card accounts. As we understand the Krispin opinion, the fact that the bank was described as the "originating entity" had no significance for the court's decision, which would have come out the opposite way if the bank, notwithstanding that it originated the credits in question, had sold them outright to a new, unrelated owner, divesting itself completely of any continuing interest in them, so that its operations would no longer be affected by the application of state law to the new owner's further administration of the credits.

[3] We are not persuaded by Munoz v. Pipestone Financial, LLC, 513 F.Supp.2d 1076 (D.Minn. 2007), upon which the defendants and the District Court also rely. Although the court found preemption applicable to an assignee of a national bank in a case analogous to Madden's suit, it misapplied Eighth Circuit precedent by applying unwarranted significance to Krispin's use of the word "originating entity" and straying from the essential inquiry—whether applying state law would "significantly interfere with the national bank's exercise of its powers," Barnett Bank, 517 U.S. at 33, 116 S.Ct. 1103, because of a subsidiary or agency relationship or for other reasons.

[4] The Change In Terms, which amended the original Cardholder Agreement, includes the following provision: "This Agreement is governed by the laws of the State of Delaware (without regard to its conflict of laws principles) and by any applicable federal laws." App'x at 58, 91.

[5] We reject Madden's contention that this argument was waived. First, although the defendants' motion for summary judgment urged the District Court to rule on other grounds, it did raise the Delaware choice-of-law clause. Defs.' Summ. J. Mem. 4 & n. 3, No. 7:11-cv-08149 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 25, 2013), ECF No. 32. Second, this argument was not viable prior to the Stipulation for Entry of Judgment due to unresolved factual issues—principally, whether Madden had received the Change In Terms.

[6] We express no opinion as to whether Delaware law, which permits a "bank" to charge any interest rate allowable by contract, see Del. Code Ann. tit. 5, § 943, would apply to the defendants, both of which are non-bank entities.

[7] Because it may assist the District Court, we note that there appears to be a split in the case law. Compare Am. Equities Grp., Inc. v. Ahava Dairy Prods. Corp., No. 01 Civ. 5207(RWS), 2004 WL 870260, at *7-9 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 23, 2004) (applying New York's usury law despite out-of-state choice-of-law clause); Am. Express Travel Related Servs. Co. v. Assih, 26 Misc.3d 1016, 1026, 893 N.Y.S.2d 438 (N.Y.Civ.Ct.2009) (same); N. Am. Bank, Ltd. v. Schulman, 123 Misc.2d 516, 520-21, 474 N.Y.S.2d 383 (N.Y.Cnty.Ct.1984) (same) with RMP Capital Corp. v. Bam Brokerage, Inc., 21 F.Supp.3d 173, 186 (E.D.N.Y.2014) (finding out-of-state choice-of-law clause to preclude application of New York's usury law).

No comments:

Post a Comment