What if a consumer is sued on a credit card debt where he does not live? There will likely be relief available: Motion to transfer venue and/or motion to dismiss the improperly filed suit; and possibly a cause of action under fair debt collection laws. This post focuses on the latter, the FDCPA in particular.

FEDERAL & STATE VENUE RULES FOR DEBT SUITS

Mandatory venue under federal law: Cardholder must be sued in county of residence

Under the FDCPA, a consumer must be sued in the county in which he or she lives or where the loan contract was signed. In credit card cases, the consumer typically signs no contract (except perhaps if the card is issued by a credit union); therefore there will typically only be one applicable venue, which would be mandatory, i.e leaving the debt collection attorney no choice in the matter. Another exception, involving location of real estate, is not applicable either, because consumer credit card debt is not a mortgage, and typically not secured at all, at least not in Texas.

If the consumer gets sued elsewhere, he or she may have a case under the fair debt collection laws in addition to being entitled to transfer of venue under the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure. -- > Motion to Transfer of Venue under TRCP.

The venue restriction on debt suits imposed by the FDCPA is found at Section 1692i(a)(2) of Title 15 of the United States Code, cited as 15 U.S.C. § 1692i(a)(2).

Mandatory venue under Texas law: Credit card debt suit must be filed in county where cardholder resides

The Texas Civil Practice and Remedies specifies where civil lawsuit may or must be brought. "May be brought" is called permissive venue and "must be brought" goes under the rubric of "mandatory venue". For consumer debt, the rules mirror the federal venue rule: the lawsuit against the consumer seeking collection of debt must be filed either where the contract was signed (if there is a signed contract) or where the consumer lives.

Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Codes also has strict rule for venue

Venue for consumer credit cases is governed by Section 15.035(b) of the Civ. Prac. & Rem Code, which mandates that venue is proper in either the county of the consumer's residence or the county in which the consumer signed the contract. The CPRC also expressly states that this provision cannot by waived by the consumer.

Enforcement of venue provision against debt collector with a record of massive violations

The Texas Attorney General recently brought an enforcement action against an attorney for routinely suing debtors in Justice Court court in Downtown Houston (JP Court of Harris County Precinct 1 Place 2) even though they lived outside the county and had no connection to Harris County. The civil action was filed by the Consumer Protection Division in the public interest and seeks a permanent injunction and hefty monetary penalities to be paid to the State of Texas. As of November 2013, it is still pending in Harris County District Court: State of Texas vs. Samara Portfolio Management LLC; Law Office of Joseph Onwuteaka, PC, and Joseph O. Onwuteaka, individually.

|

| Case Style on complaint filed by AG: State of Texas v. Samara Portfolio Management LCL TDCA Enforcement Action (above) and factual allegations section (below) |

Under the FDCPA, unless a debt collector is suing to enforce an interest in real property, it must bring any action on a debt against a consumer in the judicial district where the consumer signed the contract at issue or in the judicial district where the consumer resided when the suit was filed. 15 U.S.C. §1692i(a)(2).

Note that the federal judicial district is not coextensive with a county (a political subdivision of the state), wherefore caselaw should be researched to determine whether a venue violation can be asserted in good faith in a particular case, such as when the defendant is sued in the wrong JP court precinct within a county.

Lawsuits on behalf of corporations are mostly filed by attorneys because corporate officers who are not attorneys are not permitted to sue and sign pleadings as agents of corporate entities unless they bring the lawsuit in justice court. -- > Can a corporate entity appear in court without lawyer?

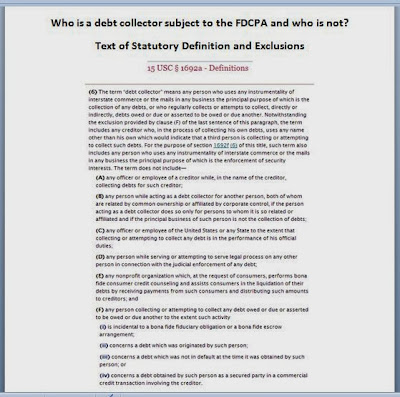

To assert a venue-violation claim against an attorney under the FDCPA, it must be shown that the attorney meets the federal definition of debt collector. The FDCPA covers attorneys, but not all attorneys under all circumstances in which a questionable or clearly prohibited act occurred (such as a violation of the federal venue rule). An attorney only faces liability under the FDCPA for such act if he or she meets the statutory definition of "debt collector". The key element of that definition is the "regularity" of the debt collection activitities. -- > When can attorneys be sued for FDCPA violations?

The FDCPA has one-year statute of limitations. Therefore, a remedy may no longer be available under the FDCPA even if a violation could easily be proven and even if the attorney meets the statutory definition. In those instance where the claim of unfair debt collection is time-barred under federal law, it may be worth considering the TDCA as an alternative.

RELATED TOPICS RELATED TO FAIR DEBT COLLECTION COMPLIANCE:

When are collection attorneys subject to liability under the FDCPA?

What is a covered debt under the FDCPA?

Texas Debt Collection and federal Fair Debt Collection Practices Act: Compare and Contrast

Texas AG civil injunction suits to enforce compliance with state fair debt collection statute