INDIVIDUAL WHO IS DUNNED OR SUED BUT DOES NOT OWE THE DEBT CAN HAVE STANDING TO BRING UNFAIR COLLECTION CLAIM UNDER FAIR DEBT COLLECTION STATUTES

Motion to dismiss in FDCPA action brought by non-debtor against prominent Texas debt collection attorney Michael Moss's law firm denied. Defendant collection law firm argued that plaintiff did not have standing to sue under FDCPA and its Texas state law counterpart: the Texas Debt Collection Act. A federal district court judge in Dallas found otherwise.

CHRISTOPHER SMITH, Plaintiff,

v.

MOSS LAW FIRM, P.C., Defendant.

United States District Court, N.D. Texas, Dallas Division.

Christopher Smith, Plaintiff, represented by Ramona Veronica Ladwig, Hyde & Swigart, Anthony Patrick Chester, Hyde & Swigart & Seyed Abbas Kazerounian, Kazerouni Law Group APC.

Moss Law Firm PC, Defendant, represented by Rebecca Anne Moss, Moss Law Firm PC & Michael Allen Moss, Moss Law Firm PC.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

SIDNEY A. FITZWATER, Senior District Judge.

In this action asserting claims for violations of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1692 et seq. ("FDCPA"), and the Texas Debt Collection Practices Act, Tex. Fin. Code Ann. §§ 392.001-.404 (West 2006) ("TDCPA"), defendant moves to dismiss under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6).

The principal question presented is whether plaintiff lacks statutory standing[1] to maintain this action because defendant's collection activities were not "directed" at him. Concluding that plaintiff has plausibly pleaded authorization to sue under the FDCPA and the TDCPA, the court denies the motion to dismiss.

I

This action by plaintiff Christopher Smith ("Smith") relates to a suit filed in Texas justice court in October 2017. At that time, defendant Moss Law Firm, P.C. ("Moss") filed suit on behalf of Barclays Bank Delaware ("Barclays") to collect a delinquent debt.[2] Smith alleges, inter alia, that the debt in dispute does not belong to him, that the lawsuit was wrongfully initiated against him, and that he informed Moss of the error. Smith also asserts that, despite the information he provided Moss (including his social security number and date of birth), Moss nevertheless proceeded with the lawsuit. Smith avers that he retained an attorney "to defend the lawsuit to avoid liability for a judgment he could not afford being wrongfully entered in his name and causing possible damage of his credit." Compl. ¶ 24. Smith was nonsuited (the Texas term for voluntarily dismissed) from the justice-court suit approximately one month after it was filed. Smith then brought this action against Moss, alleging that Moss's conduct in connection with the justice-court lawsuit violated the FDCPA and the TDCPA and that these violations caused Smith to suffer "actual damages in the form of loss of money, time, and emotional distress." Compl. ¶ 35.

Moss moves to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6), contending that Smith lacks statutory standing because the justice-court lawsuit was not directed at Smith, but was instead directed at his son, Christopher O. Smith II. Smith opposes the motion.

II

Under Rule 12(b)(6), the court evaluates the pleadings by "accept[ing] `all wellpleaded facts as true, viewing them in the light most favorable to the plaintiff.'" In re Katrina Canal Breaches Litig., 495 F.3d 191, 205 (5th Cir. 2007) (quoting Martin K. Eby Constr. Co. v. Dall. Area Rapid Transit, 369 F.3d 464, 467 (5th Cir. 2004)). To survive Moss's motion to dismiss, Smith must allege enough facts "to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face." Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007). "A claim has facial plausibility when the plaintiff pleads factual content that allows the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged." Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009). "The plausibility standard is not akin to a `probability requirement,' but it asks for more than a sheer possibility that a defendant has acted unlawfully." Id.; see also Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555 ("Factual allegations must be enough to raise a right to relief above the speculative level[.]"). "[W]here the well-pleaded facts do not permit the court to infer more than the mere possibility of misconduct, the complaint has alleged—but it has not `show[n]'—`that the pleader is entitled to relief.'" Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 679 (quoting Rule 8(a)(2)). Furthermore, under Rule 8(a)(2), a pleading must contain "a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief." Although "the pleading standard Rule 8 announces does not require `detailed factual allegations,'" it demands more than "labels and conclusions." Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 678 (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555). And "a formulaic recitation of the elements of a cause of action will not do." Id. (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555).

The Fifth Circuit has emphasized that "whether or not a particular cause of action authorizes an injured plaintiff to sue is a merits question . . . not a jurisdictional question." Camsoft Data Sys., Inc. v. S. Elecs. Supply, Inc., 756 F.3d 327, 332 (5th Cir. 2014)(quoting Blanchard 1986, Ltd. v. Park Plantation, LLC, 553 F.3d 405, 409 (5th Cir. 2008)). Accordingly, if statutory standing is lacking, the claims should be dismissed under Rule 12(b)(6). See id.; Harold H. Huggins Realty, Inc. v. FNC, Inc., 634 F.3d 787, 795 n.2 (5th Cir. 2011) ("Unlike a dismissal for lack of constitutional standing, which should be granted under Rule 12(b)(1), a dismissal for lack of prudential or statutory standing is properly granted under Rule 12(b)(6)."). The inquiry that is important in determining whether Smith has statutory standing is, in effect, "whether [Smith] has a cause of action under the statute[s]." Lexmark Int'l, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc., 572 U.S. 118, 128 (2014).

III

A

The court first considers whether Smith was required to submit evidence to show that he has statutory standing. Moss contends that Smith has the burden to establish that he has statutory standing. The court agrees that Smith must allege an adequate basis to proceed with his case and must ultimately adduce evidence that he is entitled to relief. Moss also appears to contend, however, that it has made a factual attack on Smith's standing, thus requiring Smith to prove at this stage of the case—with evidence—that he has statutory standing to bring his claims.[3] See D. Reply 3 n.2 ("[A] party may submit evidence outside the pleadings when making a factual attack on a party's prudential or statutory standing."); id. at 2 ("Plaintiff contends, without support other than his own belief, that the suit was filed against him[.]"). To the extent this is Moss's contention, the court disagrees that Moss has made (or is able to make) a factual attack that requires Smith to prove the existence of statutory standing by a preponderance of the evidence and to submit facts through some evidentiary method to sustain his burden of proof. See Gonzalez v. Gen. Motors, LLC, 2017 WL 9324466, at *4 (W.D. Tex. Nov. 7, 2017) (explaining that it would be improper to consider matters outside the pleadings in deciding a Rule 12(b)(6) motion attacking statutory standing); but see Myles v. Domino's Pizza, LLC, 2017 WL 238436, at *4, 8 (N.D. Miss. Jan. 19, 2017) (considering matters outside the pleadings in ruling on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion attacking statutory standing).

Indeed, to accept Moss's contention would be to confuse a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss with a Rule 12(b)(1) motion to dismiss. When moving to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(1) for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, a defendant can make a facial or factual challenge. See Paterson v. Weinberger, 644 F.2d 521, 523 (5th Cir. 1981). An attack is "factual" rather than "facial" if the defendant "submits affidavits, testimony, or other evidentiary materials." Id. For a plaintiff to defeat a factual attack, he must submit facts through some evidentiary method to prove the existence of subject-matter jurisdiction by a preponderance of the evidence. See id. In its reply, Moss contends that Smith "fails to meet his burden of proving statutory standing," D. Reply 3, suggesting that Moss is making a factual attack and that Smith is required to adduce evidence to meet his burden. But the court declines to impose the Rule 12(b)(1) factual challenge framework where Moss seeks dismissal for lack of statutory standing, which is properly evaluated under Rule 12(b)(6). See, e.g., Camsoft Data Sys., 756 F.3d at 332. And under Rule 12(b)(6), the court must limit its inquiry "to the complaint, its proper attachments, documents incorporated into the complaint by reference, and matters of which a court may take judicial notice." Gonzalez, 2017 WL 9324466, at *4. Thus Smith is not required to submit—nor would the court have considered—additional evidence in support of his statutory standing.

That said, "[d]ocuments that a defendant attaches to a motion to dismiss are considered part of the pleadings if they are referred to in the plaintiff's complaint and are central to [his] claim." Causey v. Sewell Cadillac-Chevrolet, Inc., 394 F.3d 285, 288 (5th Cir. 2004)(citing Collins v. Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, 224 F.3d 496, 498-99 (5th Cir. 2000)). In this case, Moss has attached Barclay's justice-court petition to its motion to dismiss. "In so attaching, [Moss] merely assists [Smith] in establishing the basis of the suit, and the court in making the elementary determination of whether a claim has been stated." Collins, 224 F.3d at 499. The justice-court case is referred to in Smith's complaint and is central to Smith's claims, and the original petition aids the court in making a determination of whether Smith has a cause of action under the FDCPA or the TDCPA. The court's Rule 12(b)(6) inquiry thus includes the complaint in this case and the justice-court petition.

B

The court next considers whether Smith lacks statutory standing under the FDCPA or the TDCPA. Moss challenges Smith's statutory standing based on its contention that its collection activities were not directed at Smith.

1

Although a primary purpose of the FDCPA is "to promote consistent State action to protect consumers against debt collection abuses," the FDCPA does not limit recovery to debtors. See 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e). Indeed, 15 U.S.C. § 1692k, which defines civil liability for FDCPA violations, provides that "any debt collector who fails to comply with any provision of [the FDCPA] with respect to any person is liable to such person[.]" Id. § 1692k(a). District courts in this circuit and others have recognized that "under certain circumstances, third-party, non-debtors have standing to bring claims under the FDCPA." See Prophet v. Myers, 2009 WL 1437799, at *3 (S.D. Tex. May 21, 2009) (compiling cases).

Similarly, the TDCPA is intended to protect consumers, but does not limit recovery to consumers. Tex. Fin. Code Ann. § 392.403 creates a private right of action for TDCPA violations and provides: "A person may sue for: actual damages sustained as a result of a violation of this chapter." Tex. Fin. Code Ann. § 392.403(a)(2). According to the Fifth Circuit, "persons who have sustained actual damages from a [TDCPA] violation have standing to sue." McCaig v. Wells Fargo Bank (Tex.), N.A., 788 F.3d 463, 473 (5th Cir. 2015) (citing Tex. Fin. Code Ann. § 392.403(a)(2)).

2

Moss does not assert that non-debtor plaintiffs can never state a claim under the FDCPA and the TDCPA. But it contends that courts allow non-debtor actions "only when conduct is abusive, directed at the non-debtor, and results in actual damages." D. Mot. 6. Moss maintains that it "did not direct any debt collection efforts at [Smith]," and it points to the account statement attached to the justice-court petition, which bears the name "Christopher O[.] Smith II," not "Christopher O. Smith." Id. at 6-7. Smith responds that Moss's collection activities were directed against him because, inter alia, the justice-court petition alleged that Smith owed the debt, and Moss proceeded with the lawsuit despite being told that Smith was the wrong party. Without suggesting a view on how the court would decide a motion for summary judgment or how a jury would evaluate the merits of Smith's claims, the court concludes that Smith's case should not be dismissed for lack of statutory standing, as Moss contends.

At this stage of the case, the court accepts Smith's well-pleaded facts as true and evaluates "whether [Smith] has a cause of action under the statute[s]." Lexmark Int'l, Inc., 572 U.S. at 128. To state a claim under the FDCPA, Smith must plausibly plead that a debt collector has failed to comply with a provision of the FDCPA with respect to him. See 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a). Smith alleges that Moss sought to collect a debt that Smith did not owe to Barclays; that Moss initiated a lawsuit against Smith to collect this alleged debt; that Smith informed Moss of the error; and that Moss nevertheless continued to pursue the lawsuit against Smith. Moss is correct that the account statement attached to the justice-court petition bears the name "Christopher O[.] Smith II." But that fact does not undermine Smith's allegations of collection activity directed at him—especially considering that the caption and party description within the justice-court petition bear the name "CHRISTOPHER O SMITH," without the "II" addition. Reading Smith's complaint and the justice-court petition under the proper standard, Smith has adequately pleaded that Moss's actions were directed toward him.

Turning to the TDCPA, the Fifth Circuit has rejected a requirement that debt collection efforts be "directed" or "targeted" at a particular individual for the individual to have standing to sue under the TDCPA. See McCaig, 788 F.3d at 474. Moss cites several district court cases, such as Prophet, 2009 WL 1437799, and Ledezma v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., 2014 WL 6674285 (S.D. Tex. Nov. 24, 2014), that impose a targeting requirement, but these cases predate McCaig and, more important, McCaig expressly rejects the targeting rule applied in Prophet. See McCaig, 788 F.3d at 474 & n.3. The Fifth Circuit explained that, "[i]n rejecting this rule, it is sufficient to observe that Section 392.403(a)(2) contains no targeting requirement and that the district courts that have adopted the rule did not base their standing analyses on the text of Section 392.403(a)(2)." Id. at 474. Thus, as instructed by the Fifth Circuit, this court's duty is to apply existing state law, which suggests that the rule is that "persons who have sustained actual damages from a [TDCPA] violation have standing to sue." Id. at 473 (citing Tex. Fin. Ann. Code § 392.403(a)(2)). Smith alleges that Moss violated Tex. Fin. Code Ann. § 392.304(a)(19), and that, as a result of Moss's actions, he has "suffered actual damages in the form of loss of money, time, and emotional distress." Compl. ¶ 35. These allegations are sufficient to plausibly plead Smith's authorization to sue pursuant to the TDCPA.

Accordingly, Smith has alleged a plausible basis to proceed under the FDCPA and the TDCPA; his claims do not fail at the motion to dismiss stage for want of collection activities directed at him.

* * *

For the reasons explained, the court denies Moss's motion to dismiss.

SO ORDERED.

[1] Although "statutory standing" is an imperfect label that can be misused because it is not truly a "standing" doctrine, the term is used by the parties throughout their briefing, and the court is satisfied that, in this case, it is being used to refer to the correct inquiry: whether the plaintiff has pleaded a plausible cause of action under the statutes. See Lexmark Int'l, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc., 572 U.S. 118, 128 & n.4 (2014).

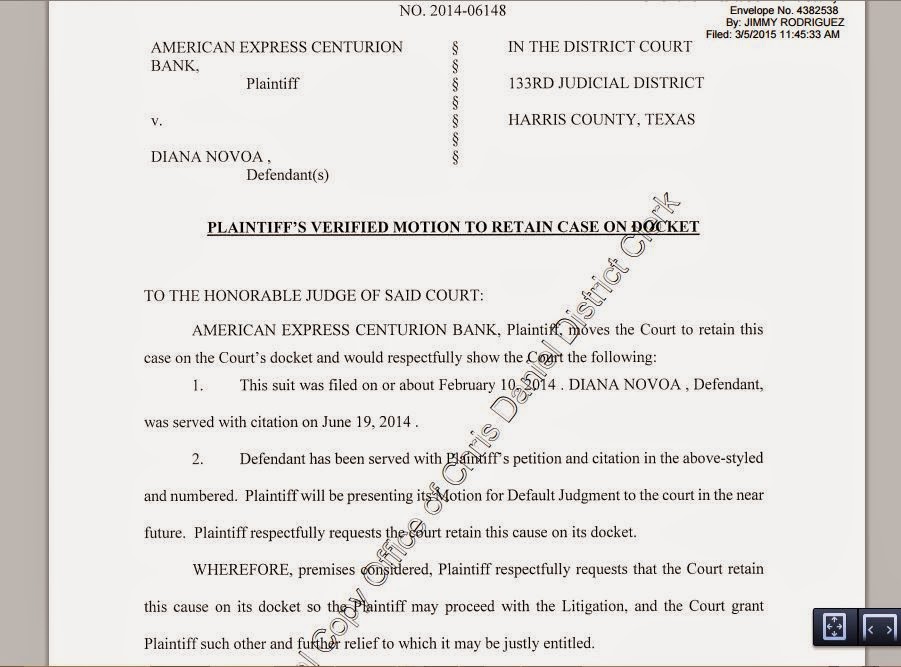

[2] The lawsuit was captioned Barclays Bank Delaware v. Christopher O Smith, Case No. JX1700978H, in the Justice Court, Precinct 1, Place 1, of Dallas County, Texas.

[3] The court recognizes that, in Superior MRI Services, Inc. v. Alliance Healthcare Services, Inc., 778 F.3d 502, 504 (5th Cir. 2015), the Fifth Circuit affirmed a district court decision in which a defendant "brought a factual attack on [plaintiff's] prudential standing." The court also recognizes that the terms "prudential standing" and "statutory standing" are sometimes used interchangeably, which may have prompted Moss to cite Superior MRI Services and posit that "[t]he Fifth Circuit has made it clear . . . that a party may submit evidence outside the pleadings when making a factual attack on a party's prudential or statutory standing." D. Reply 3 n.2. But Superior MRI Services did not involve statutory standing. In fact, the Fifth Circuit panel explicitly discussed the fact that the "type of prudential standing requirement" at issue in that case (third-party standing) was different from the type that was before the Supreme Court in Lexmark (statutory standing). See Superior MRI Servs., 778 F.3d at 506. Thus the court does not agree that Superior MRI Services should be applied to cases involving statutory standing.