CONSUMER CONTRACTS DON'T MATTER WHEN APPELLATE COURTS CREATE CASELAW TO ALLOW CIRCUMVENTION

Much of the discussion about the state of American consumer law, including the ongoing controversy over the Restatement of the Law of Consumer Contracts, and its reliance on quantitative surveys of caselaw of questionable quality, center on issues surrounding consumer contracts at the front end:

Questions such as the manner in which a contract is formed in the first instance, and how terms are later modified; whether the specific terms applicable to the transaction are disclosed to the consumer in a meaningful and understandable manner; and whether they are excessively one-sided, oppressive, or unconscionable.

CONSUMERS AS CLAIMANTS (PLAINTIFFS)

One major underlying concern is that consumers’ ability to bring claims against businesses may be jeopardized, that the scope of rights a consumer has under such a contract may be unduly limited, such as through mandatory arbitration and class-action waiver clauses, and that consumers may be prevented from vindicating their rights—including statutory rights that come into play based on the nature of the transaction--in an effective manner.

A related issue is whether consumer contracts are drafted to effectively preclude relief that could otherwise be obtained through class actions. This is obviously of great importance in instances of large-scale wrongful business conduct where the value of each claim any single consumer might have is too small to make it economically feasible to bring such claim in an individual action.

Questions such as the manner in which a contract is formed in the first instance, and how terms are later modified; whether the specific terms applicable to the transaction are disclosed to the consumer in a meaningful and understandable manner; and whether they are excessively one-sided, oppressive, or unconscionable.

CONSUMERS AS CLAIMANTS (PLAINTIFFS)

One major underlying concern is that consumers’ ability to bring claims against businesses may be jeopardized, that the scope of rights a consumer has under such a contract may be unduly limited, such as through mandatory arbitration and class-action waiver clauses, and that consumers may be prevented from vindicating their rights—including statutory rights that come into play based on the nature of the transaction--in an effective manner.

A related issue is whether consumer contracts are drafted to effectively preclude relief that could otherwise be obtained through class actions. This is obviously of great importance in instances of large-scale wrongful business conduct where the value of each claim any single consumer might have is too small to make it economically feasible to bring such claim in an individual action.

CONSUMER CONTRACTS

AT THE BACK END – WHEN CONSUMERS BECOME LAWSUIT TARGETS

Much more, however, is at stake for individuals at the back-end,

when the business has a claim against a consumer, and takes the consumer to court.

And that’s where consumer contracts matter too. At least in theory.

And that’s where consumer contracts matter too. At least in theory.

A debt collection claim is, in essence, a breach of contract

claim because the creditor’s complaint is that the consumer has defaulted, i.e.

has not made periodic payments as promised, which takes two basic forms: (1) a failure

to make regular installment payments as they become due under the amortization

schedule of a retail installment contract or (2) a failure to make monthly

minimum payments computed based on a formula contained an agreement governing open-end

credit such as a credit card account. In the latter case, the minimum payment will

typically consist of a percentage of the revolving balance and current finance

charges, which may include other charges (such as a late fee or over-limit fee)

in addition to the newly accrued interest and any past-due amount.

To prove such a breach-of-contract claim under Texas common

law, a plaintiff must adduce sufficient evidence on a several essential

elements: (1) a valid contract, (2) performance by the plaintiff or tender of

performance, (3) breach by the defendant, and (4) damages caused by breach.

In order to obtain a judgment against a consumer, a creditor

would, under long-standing caselaw, have to produce competent evidence on each

element. If the creditor fails to do so, or if the proffered evidence is of

questionable quality and therefore subject to evidentiary objections and

exclusion, the consumer may have a viable defense to the lawsuit.

The reality, however, is different. At least in Texas, appellate

courts have made it much easier for creditors to obtain judgments against

former customers by relaxing conventional proof requirements in debt collection

cases, and by allowing creditors to avoid the proof requirements applicable to a breach-of-contract

claim altogether, thus rendering the contract, and whatever terms it may contain,

immaterial.

CIRCUMVENTION OF

PROOF REQUIREMENTS APPLICABLE TO BREACH OF CONTRACT

Starting in 2008 with an opinion issued by the Dallas

Court of Appeals, Texas courts have allowed creditors to circumvent the proof

requirements of a breach-of-contract claim by bringing the collection action as

a common-law “account stated” claim instead, or in the alternative. See Dulong v. Citibank (South Dakota),

N.A., 261 S.W.3d 890, 893 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2008, no pet.).

"ACCOUNT STATED" ADAPTED FOR CREDIT CARD

DEBT COLLECTION IN TEXAS

When a creditor proceeds on an account-stated theory, it no

longer has to provide even a copy of a boilerplate credit card agreement. Credit

card statements alone will do.

See à The Account Stated Theory and the lowering of proof requirements in credit card debt collection cases; --> Resurrection of account-stated for credit card debt collection in Texas.

See à The Account Stated Theory and the lowering of proof requirements in credit card debt collection cases; --> Resurrection of account-stated for credit card debt collection in Texas.

Also see: Emanuel J. Turnbull, Account Stated Resurrected: The Fiction of Implied Assent in Consumer Debt Collection, 38 VT. L. REV. 339, 340 (2013)

Several other courts of appeals have jumped on the bandwagon

without re-examining the validity of the suit-on-account theory for collection

of a bank debt that does not involve sale of goods or services, thus lowering the

proof requirements for credit card debt plaintiffs, and depriving the

defendants of any benefits that might accrue from the existence of a written

contract. See, e.g., McFarland v. Citibank (S.D.), N.A., 293 S.W.3d 759, 764

(Tex. App.-Waco 2009, no pet.) ("Thus, we join our sister courts in

holding that account stated, and not a suit on a sworn account, is a proper

cause of action for a credit card collection suit because no title to personal

property or services passes from the bank to the credit card holder."); Jaramillo v. Portfolio Acquisitions, LLC, No. 14-08-00939-CV, 2010 WL 1197669, at *7 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] Mar. 30, 2010, no pet. h.) (mem. op.); Butler v. Hudson & Keyse, L.L.C., No. 14-07-00534-CV, 2009 WL 402329, at *3 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] Feb. 19, 2009, no pet.) (mem. op.); also see Houle v. Capital One Bank (USA), NA., No. 08-16-00234-CV (Tex.App.- El Paso, 2018, pet. filed) (affirming summary judgment for credit card bank on two theories).

|

| McFarland v. Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., 293 S.W.3d 759 (Tex.App.-Waco 2009, no pet.) |

QUANTUM MERUIT REMEDY ALSO MIS-APPROPRIATED FOR CONSUMER DEBT COLLECTION - FOR THE BENEFIT OF A VULTURE FUND, NO LESS

One Texas court of appeals has gone so far as to bless quantum meruit as an alternative theory for the collection of a bank debt, even though quantum meruit is an equitable theory and is generally precluded when a contract governs the parties’ relationship because a suit to enforce the contract provides an adequate legal remedy.

In 2008, the Fourteenth Court of Appeals jumped on quantum meruit to accommodate a debt-buyer entity that was at that time a prolific litigant in court all around Texas, but had not adduced sufficient evidence from the original creditor to prevail on its breach-of-contract claim in the case that came before the court. See McElroy v. Unifund CCR Partners, No. 14-07-00661-CV, 2008 WL 4355276 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] Aug. 26, 2008, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Quantum meruit generally applies only to

claims based on the sale of goods or provision of services not paid for. A bank does not

sell goods or services. Instead, it makes its money by charging interest on the

extension of credit and on fees paid by merchants that accept their cards. Interest

is not compensation of services, and the goods or services charged on a credit

card are provided by third parties. These purchases are financed by the bank, rather

than the bank acting as seller. The only component of a balance on a credit

card account that arguably constitutes compensation for a service provided by

the bank to its customer would be an annual membership fee or monthly service

charge. But even that is debatable, at least under federal law governing

consumer credit, including the federal definition of what constitutes finance charges.

A memorandum opinion issued by the same Houston-based appellate court in a subsequent credit card collection case brought by a bank (rather than a debt buyer) likened the case to McElroy in that it was undisputed that “there was a credit-card agreement of some kind,” but did not take issue with the blessing of the quantum meruit doctrine for credit card debt collection. See Ayers v. Target Nat'l Bank, No. 14-11-00574-CV, 2012 WL 3043043 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] July 26, 2012, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing summary judgment granted in favor of bank on breach-of-contract theory).

Ayers’ discussion of McElroy solidifies the conclusion that the quantum meruit claim had been permitted even though the breach-of-contract cause of action was available, and could have been pursued with proper evidence. By affirming the judgment for the creditor in McElrod despite the creditor’s failure to prove up the terms of the underlying credit card agreement, the Fourteenth Court of Appeals essentially condoned and excused the debt buyer’s failure to adduce the requisite type and amount of proof. It blessed the circumvention of those proof requirements through an alternative theory that had--at least until then--been inapposite and unavailable because quantum meruit is an equitable remedy incompatible with the existence of a contract governing the parties’ relationship.

But once a court of appeals makes an error of law, the same court can then defend and repeat the error by treating it as a prior ruling with the force of precedent.

That has not happened with McElroy, but it did happen with the Dulong precedent from Dallas, which has been cited and relied upon numerous times by appellate courts since. Account Stated is routinely pleaded by some creditors in mass litigation in the trial courts. Very few such cases reach the courts of appeals these days. Some banks have also embraced the new opportunity.

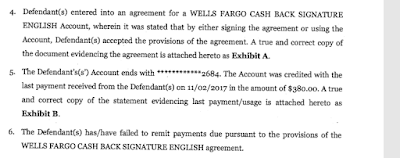

Wells Fargo, for example, now pleads an account-stated count in addition to their cause of action for breach of contract.

RELAXATION OF PROOF

REQUIREMENTS FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT ITSELF

In addition to providing a work-around when a creditor cannot find a contract as a predicate for a breach-of-contract claim, Texas courts have also lowered the standards that generally apply in contract cases to accommodate credit card issuers and purchasers of charged-off accounts. There is now, in effect, a special interest jurisprudence for the benefit of creditors that has carved out its custom exceptions from general rules of law and procedure.

Many courts no longer hold plaintiffs to the burden of actually having to prove that a boilerplate agreement attached to a summary judgment affidavit

is the agreement that was provided to the customer and subsequently accepted by

card use. Instead, they consider conclusory affidavit testimony to the effect that

“Exhibit A is a true and correct copy of the applicable agreement” sufficient. See, e.g., Houle v. Capital One Bank (USA),

NA. No. 08-16-00234-CV (Tex.App.- El Paso, 2018, pet. filed).

One court saw no problem with the fact that the date printed

on the generic agreement did not match the date referenced by the affiant as

the date of contract-formation by card use, reasoning that the bank had the

right to change the terms (as shown on the face of the challenged agreement)

and that the defendant accepted the more recent version by continued card use.

See Wakefield v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., No. 14-12-00686-CV, 2013 Tex. App.

LEXIS 14018 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.]. Nov. 14, 2013, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Although, with the appellate court's help, Wells Fargo defeated the pro se appeal, the bank subsequently changed its affidavit template, which no longer includes the date of card use as a relevant contract-formation fact. See excerpt from a more recent case below:

|

| Affidavit excerpt from Wakefield: Approximate Contract-formation Date |

Although, with the appellate court's help, Wells Fargo defeated the pro se appeal, the bank subsequently changed its affidavit template, which no longer includes the date of card use as a relevant contract-formation fact. See excerpt from a more recent case below:

|

| Excerpt from Wells Fargo affidavit in a recent filing: Date of last payment reported, but no date for contract formation by card use |

CONTRACT-FORMATION PROOF IN DISPUTES OVER ARBITRATION

Interestingly, the contract-formation analysis with respect

to notice of terms is much more refined when it comes to acceptance of an arbitration

agreements by an employee (by continuing to work after notice) and when the which-version-is-the-controlling-contract

issue surfaces in other types of litigation involving banks and their customers.

As for formation of an agreement to arbitrate in the employment context, see Kmart Stores of Tex., L.L.C. v. Ramirez, 510 S.W.3d 559, 565 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2016, pet. denied) (where employer provided evidence that employee had logged on to computer and received notice of arbitration agreement, employee bore burden of raising a fact issue contesting formation, which she met by filing a sworn denial of notice); Stagg Restaurants, LLC v.. Serra, No. 04-18-00527-CV (Tex.App.- San Antonio, Feb. 13, 2019, no pet.) (trial court's denial of motion to compel arbitration affirmed in interlocutory appeal where employer failed to prove notice of arbitration provision in occupational injury plan document to employee who later brought work-related injury suit).

As for different sorts of bank-customer litigation, see In Re Comerica, No. 14-16-00418-CV (Tex.App.- Houston [14th Dist.] Jun. 30, 2016)(concluding that “Comerica has not established that the trial court clearly abused its discretion by ordering Comerica to withdraw its application to arbitrate the claim against it with JAMS because the record contains no evidence that Comerica mailed written notice of the amended Contract and its text to [customers] or that [customers] by some other means agreed to the amended Contract with the arbitration provision.”).

As for formation of an agreement to arbitrate in the employment context, see Kmart Stores of Tex., L.L.C. v. Ramirez, 510 S.W.3d 559, 565 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2016, pet. denied) (where employer provided evidence that employee had logged on to computer and received notice of arbitration agreement, employee bore burden of raising a fact issue contesting formation, which she met by filing a sworn denial of notice); Stagg Restaurants, LLC v.. Serra, No. 04-18-00527-CV (Tex.App.- San Antonio, Feb. 13, 2019, no pet.) (trial court's denial of motion to compel arbitration affirmed in interlocutory appeal where employer failed to prove notice of arbitration provision in occupational injury plan document to employee who later brought work-related injury suit).

As for different sorts of bank-customer litigation, see In Re Comerica, No. 14-16-00418-CV (Tex.App.- Houston [14th Dist.] Jun. 30, 2016)(concluding that “Comerica has not established that the trial court clearly abused its discretion by ordering Comerica to withdraw its application to arbitrate the claim against it with JAMS because the record contains no evidence that Comerica mailed written notice of the amended Contract and its text to [customers] or that [customers] by some other means agreed to the amended Contract with the arbitration provision.”).

![In Re Comerica, No. 14-16-00418-CV. (Tex.App.- Houston [14th Dist.] Jun. 30, 2016) (agreement on arbitration not proven) In Re Comerica, No. 14-16-00418-CV. (Tex.App.- Houston [14th Dist.] Jun. 30, 2016) (agreement on arbitration not proven)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhEduWjrR_q6ugm1xgnLO2e14JWS7TZAjthBmMqrNElpR66y8UUtGoJ6G2sGpiJZfIWu3yQB3qal-inEdYj8dpYm2TeKkHH51m_iG60CgkEmKWKMyQzLkESUjZZmA5nH0NZZL5W8PxhkXMF/s400/Arb+caselaw+-+In+Re+Comerica+Bank+%2528Tex.App.-Houston+2016%2529.JPG) |

| In Re Comerica, No. 14-16-00418-CV (Tex.App.- Houston [14th Dist.] Jun. 30, 2016) (agreement on arbitration not proven) |

THIS IS THE CONTRACT THAT APPLIES TO THE DEFENDANT; TAKE MY WORD FOR IT

There are significant differences among major credit card

issues on whether the credit card agreement offered as evidence in a collection

suit contains any indicia that link it to a specific account or the specific account

holder.

American Express used to rely generic agreements like other

major card issuers, but years ago switched to a practice of issuing cardholder

agreements that are dated, and also contain the name of the account holder

(including the name of the business for business cards), the account ending

digits, and the type of account. The unique identifying information is printed

in the top section of the first page of the cardmember agreement, which

consists of two parts. One part sets forth the account-specific pricing terms

while the other part contains the standard (invariant) terms that also apply to

other cardholders within the same customer segment. Those terms include a Utah

choice of law clause and regularly also encompass some form of an arbitration

agreement.

Discover Bank’s customer agreements do not contain

information identifying accounts by numbers or customers by name, but

references the version of the agreement (called “Terms Level”) within the body

of the affidavit of its servicer, which is a variable data field in the

template along with other case-specific data such as name of cardholder and

amount of the outstanding balance for which the Bank seeks judgment.

The Customer Agreements attached by Wells Fargo Bank, by

contrast, do not contain any account or customer-specific particulars. Nor does

Wells Fargo even attach the “Important Terms of Your Account” document that sets

forth the account-specific cost-of-credit disclosures required under the Truth

in Lending Act. A number of appellate cases, even from otherwise creditor-friendly

courts of appeal, hold that the creditor must prove the cost terms because they

are essential contract terms, but adherence to this long-standing rule of law

is also eroding.

Texas court of appeals cases that found that proof of credit terms (or derivation of balance, which requires proof of interest) was lacking or insufficient:

Uribe v. Pharia, LLC, No. 13-13-00551-CV, 2014 WL 3555529 (Tex.App.-Corpus

Christi July 17, 2014) (mem. op.) (collecting cases).

- Williams v. Unifund CCR Partners Assignee of Citibank, 264 S.W.3d 231, 236 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 2008, no pet.)(holding evidence was insufficient to establish the terms of a valid contract as a matter of law where creditor failed to produce actual credit-card agreement or any other document that established the agreed terms, including the applicable interest rate or method for determining finance charges);

- Tully v. Citibank (S.D.), N.A., 173 S.W.3d 212, 216-17 (Tex. App.-Texarkana 2005, no pet.) (holding evidence insufficient to show interest rate charged was agreed on where the only evidence was the rates specified in monthly statements);

- Hooper v. Generations Community Federal Credit Union, No. 04-12-00080-CV, 2013 WL 2645111, at *3 (Tex. App.-San Antonio June 12, 2013, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing judgment for creditor where cardholder agreement was not offered into evidence and there was no evidence establishing debtor's specific obligations under an agreement);

- Colvin v. Tex. Dow Employees Credit Union, No. 01-11-00342-CV, 2012 WL 5544950, at *6 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] Nov. 15, 2012, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing summary judgment for creditor where creditor failed to offer the original agreement, monthly statements, or other evidence establishing how it calculated its alleged damages);

- Martin v. Federated Capital Corp., No. 01-12-00116-CV, 2012 WL 4857835, at **2-3 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] Oct. 11, 2012, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing summary judgment for creditor where creditor's evidence failed to explain how it calculated its damages);

- Ayers v. Target National Bank, No. 14-11-00574-CV, 2012 WL 3043043, at **2-4 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] July 26, 2012, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing summary judgment for creditor where creditor failed to present cardholder agreement and a portion of the form language on the credit-card application was illegible and form language was in Spanish);

- Wande v. Pharia, No. 01-10-00481-CV, 2011 WL 3820774, at *5 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] Aug. 25, 2011, no pet.) (mem. op.) (reversing summary judgment for creditor where creditor presented the cardholder agreement but important portions of the agreement were illegible, including a section entitled "Finance Charges," and creditor presented no evidence regarding the calculations it used to arrive at claimed outstanding balance);

- Jaramillo v. Portfolio Acquisitions, LLC, No. 14-08-00939-CV, 2010 WL 1197669, at **5-6 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] March 30, 2010, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding evidence insufficient to establish a valid contract where card member agreement was entered into evidence, but many of its material terms were missing; "This court and its sister court have drawn a distinction between cases where a card member agreement is entered into evidence and where there is no card member agreement.")

FUTURE POST: THE LOWERING OF

EVIDENTIARY STANDARDS IN CONSUMER DEBT COLLECTION CASES

[ forthcoming ]